Enslavement

Enslavementto freedom

Study Areas

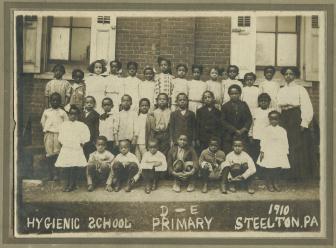

The Hygienic School, Steelton, Pennsylvania

|

The following article was made possible by the Friends of Midland organization, which contributed photographs, information and primary research materials from their archives. Originally formed to rescue and rehabilitate the historic Midland Cemetery, the Friends of Midland also have an interest in local African American history, including the Hygienic School.They are very interested in hearing from former students of the Hygienic School, and can be contacted at the following address: |

|

Built on the steep hillsides that roll out of Swatara Township down to the Susquehanna River, Steelton, Pennsylvania unfolds dramatically from Harrisburg's southern limits like a giant carpet of industrial structures. Its smokestacks, power lines and water towers rise from the edge of the river, looking for all the world as if they were put there solely to hold the hillsides full of row homes and churches from sliding all at once into the water. Perhaps, in a historical sense, that is what they were meant to do. Unlike Middletown, its neighbor to the south, Steelton is not a river town. It is a steel town, built by and for that industry. It arose in 1866 on the extensive farmland of Harrisburg's Kelker family, a town born of the Pennsylvania Railroad's need for steel rails to extend its ever expanding lines. The post-Civil War boom gave the new Pennsylvania Steel Company, utilizing the revolutionary Bessemer process, the necessary impetus for growth and success, and in a short time it crept to a fully-integrated industrial complex, four miles long.1 The Kelker brothers used money from the sale of their family farm to buy up the land east of the rising mills and divided it into lots for worker housing, and those workers came.2 Among them were African Americans, whose numbers swelled in the late 1800's as increased production caused an intense need for steel workers. Pennsylvania Steel Company, and its 1916 successor Bethlehem Steel Corporation, both sent recruiters into the South, who in turn sent Black workers back to the plant, often in times of labor unrest. Bethlehem Steel alone, having invested 15 million dollars in the plant just before World War I, sent nearly 600 southern Blacks to work at the modernized mills during that war. They were housed in barracks built and run by the corporation. Many more newly-arrived African American workers occupied shanties along the old Pennsylvania Canal and along Adams Street.3 Steelton's African American community thrived as one of many cultural and ethnic groups that made up the town. Other groups--Croats, Slavs, Germans, Italians--were quickly assimilated into Steelton's multi-ethnic society. The ugly realities of racism, however, kept African Americans segregated into separate neighborhoods, and separate social institutions, including schools.

The HygienicHill School received its name from its location on Hygienic Hill, at Bailey Street between Adams and Ridge Streets.4 Steelton newspaper editor Peter Sullivan Blackwell conceived of the school as a way to provide a quality education for the African American community's children. It would also provide employment for Black schoolteachers, who were denied employment in the white schools.5 Blackwell originally instituted a night school in the basement of the Monumental A.M.E. Church in the mid-1880's, and by 1890 was seeking larger accommodations for the expanding student body. One of the first organized protests by Steelton's Black population against the discriminatory practices of the school board was in 1890 when the board attempted to place the Black students in an old, ramshackle hall. Blackwell and another Adams Street resident, Joseph Hill, organized the American Protective Association to oppose the school board's plans. The Association demanded that appropriate school rooms be built for the community's Black children, or that they be given separate rooms in the high school. A compromise was made when someone suggested that the two rooms in the Hygienic Hill School could be used.6

Within a few years it became evident that the circa 1881 Hygienic School building was too small for the growing number of children enrolled. The Steelton Press, Blackwell's newspaper, took up the call for improvements to the aging structure, but it would take four years of protests before the local school board would expend funds to add six new classrooms to the Hygienic School.7

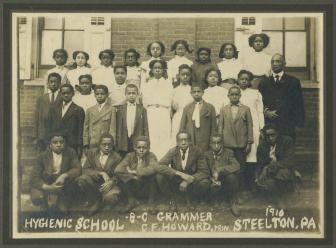

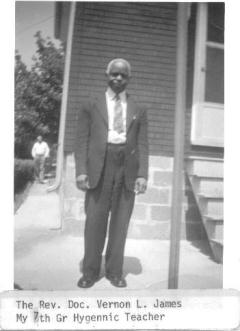

Highlights of Mr. Howard's tenure include a fierce devotion to encouraging excellence in his students."He disliked mediocrity," wrote John B. Yetter in Steelton, Pennsylvania; Stop - Look - Listen (Harrisburg, PA, 1979). "Many of his teachers were his former pupils; there was scholarly Vernon James ... strict Edward Carey ... witty John Fields ... to name a few. His school was among the first in Pennsylvania to add Black history to its curriculum." At left, Hygienic School principal Charles F. Howard is shown in this enlargement taken from the class picture above. According to old handwritten notes in the Friends of Midland Archives, Howard was the first African American student to graduate from Steelton High School, in 1885. He almost immediately began teaching at the new school begun by newspaper editor Peter Sullivan Blackwell for Steelton's Black children. This school, originally located in the basement of the Monumental A.M.E. church, became the Hygienic School a few years later, and Howard became its principal. (Photograph courtesy of the Friends of Midland Archives) The commitment to education shown by Steelton's African American community is embodied in the strong role of the Black churches in

support of the Hygienic School. The Hygienic School began as a night school in the basement of a local Black church, and graduation ceremonies for Hygienic students completing the eighth grade were often held at local churches. When Steelton's Black citizens found that their children who persevered through Hygienic School teacher Doctor Vernon R. James was one of the founders of the Douglass Association, an alumni association for Black Steelton High School graduates who were barred by racism from joining the whites-only Steelton High Alumni Association. The Douglass Association was active in the community and vigorously supported education for African Americans. A typewritten caption on the reverse of this photograph reads "A man of renown, knowledge and world traveler, held back from the heights attained with the qualifications of success because of his color in his time." Dr. James died in 1968. For the obituary of Rev. Dr. Vernon R. James, please click here. For another photo of Dr. James at a Memorial Day event, please click here.

The Hygienic School continued to have an all-Black enrollment at least through the 1960's as the Supreme Court mandated integration of Pennsylvania public schools was instituted throughout the commonwealth. Although the building was torn down in 1974, Steelton residents and school alumni hold fond memories of the school and its teachers. Many recall the close relationship between the teachers and students, and believe that their education was equal to, if not better than, that received by the students at better funded and equipped white schools.10 "There's no one who attended that school that isn't proud to say so," declared Hygienic School alumni Clayton Carelock at a recent discussion about the school's history.11 Indeed, instead of being a sore reminder of racial segregation, the Hygienic School stood as a proud symbol of a community's commitment to education and self-reliance. Sources1. Gerald G. Eggert, Harrisburg Industrializes: The Coming of Factories to an American Community (The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA, 1993), pages 91-97. (back to text) 2. Ibid. p. 94. (back to text) 3. John E. Bodnar, "Peter C. Blackwell and the Negro Community of Steelton,1880-1920," in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography XCVII (April, 1973), page 200. (back to text) 4. American Mosaic, Segregation in Steelton, Pennsylvania, Dickinson University. (back to text) 5. Interview with Barbara B. Barksdale, Clayton C. Carelock and Lonnie Dodd, July 24, 2002.(back to text) 6. Bodnar, page 203. (back to text) 7. Ibid.; American Mosaic. (back to text) 8. "Roll of Colored Graduates of Steelton H.S.," manuscript notebook, undated but believed to be circa 1940. Collection of Clayton C. Carelock. In addition to documenting 284 names of Black graduates of Steelton High School from 1885 to 1940, this notebook also includes the lists "Former Teachers in the Hygienic School," and "Other Outstanding Graduates." See the list of other Steelton articles below for transcriptions of this notebook.(back to text) 9. Bodnar, pages 202-204. (back to text) face="Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif"10. American Mosaic.(back to text) 11. Interview with Barbara B. Barksdale, Clayton C. Carelock and Lonnie Dodd, July 24, 2002.(back to text) Other Steelton Articles: |

Afrolumens Home Page | Enslavement | Underground Railroad | 19th Century | 20th Century

four more years at Steelton High School were barred from

joining the all-white alumni association, they formed the Douglass Association. Hygienic School educators Charles F. Howard, Howard H. Summers, and Vernon R. James, and community leader Franklin Jefferson named the association for Frederick Douglass, with the published aims of encouraging education among the local Black community and the "mental and moral improvement of its members."

four more years at Steelton High School were barred from

joining the all-white alumni association, they formed the Douglass Association. Hygienic School educators Charles F. Howard, Howard H. Summers, and Vernon R. James, and community leader Franklin Jefferson named the association for Frederick Douglass, with the published aims of encouraging education among the local Black community and the "mental and moral improvement of its members." Third grade Hygienic School teacher Shellon Terrell James, wife of Dr. Vernon R. James.

Third grade Hygienic School teacher Shellon Terrell James, wife of Dr. Vernon R. James.