Study Areas:

Underground Railroad

Chronology of Underground Railroad Activity in Harrisburg, with Related Activity, Relevant Figures and Events

Early Period, 1727-1780

Circa 1707 John Harris settles near the confluence of the Paxtang Creek and the Susquehanna River, either bringing with him from Conoy (modern Bainbridge), or soon thereafter acquiring, an enslaved man, Hercules.

c1707- 1718 According to Harris family history, Hercules rescues John Harris from a party of angry Native Americans. Regardless of whether that story is true, Harris eventually rewards his slave by stipulating in this will that he is to be manumitted and allowed to live on a nearby tract of land.

1733 Harris begins his ferry and trading operation, bringing numerous travelers to this area.

1746 John Harris Sr. dies. In his will, he allows for the manumission of his enslaved man Hercules, who becomes the first free African American in this area. The land on which Hercules is allowed to live eventually develops into Judystown, the first African American neighborhood in Harrisburg.

1758 Tax returns for "ye West Side of Derry" Township, in 1758, report the Widow Sample "deeded 100 acres to 2 Neagors, 1 aged 60 the other 12 years." These unidentified Blacks seem to be the first African American property holders in what would be Dauphin County. (transcribed in Egle's Notes and Queries, LXVI, First and Second Series, Volume I, page 444.)

1766 Advertisements for freedom seekers, then termed runaway or fugitive slaves, in and about Paxton Township, Lancaster County, appear in The Pennsylvania Gazette. (learn more)

1780 Pennsylvania's revolutionary legislature passes the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780, which creates two classes of enslaved persons, those bound for life, and those bound until the age of 28. This sets the stage for a growing free Black population. (learn more)

Post Revolution to 1830

1786 A "List of Taxable Inhabitants of Dauphin County For the Year 1786" lists in "Lewisburg" (Louisbourg, later Harrisburg) the following African Americans: James at Hershaws, and Francis Lauret.

1790 Listed in Dauphin County is "Robert Clinch a free Negroe." A slave, whose age and sex is not given, also lives in Clinch's household. (First Census of the United States, 1790, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, Series M637, Roll 8, Page 173)

1800 Federal census lists 16 enslaved persons held in Harrisburg, out of 85 in the county. There are no identifiable free Black families living independently, but there are 45 free Black persons living in the homes of white employers.

1802 Harrisburg is listed in a Martinsburg, Virginia broadside advertisement as a probably destination for escaped slave Jerry Arthur, of Jefferson County, Virginia. Arthur, who was called "Briscoe's Jerry" in slavery, escaped in December 1799, taking with him extra clothing and a forged pass.

1810 Federal census lists seven identifiable free Black families (36 persons) in Harrisburg, and 45 other free Blacks living in white households. (learn more)

1817 An "African Church" is chartered and Thomas Dorsey, under the auspices of the African Methodist Society, founds a school for local African American children, both enslaved and free, the first of many social institutions marking the rise of a vibrant free Black community.

1820 Federal census schedules show 34 free Black families (117 persons) living independently in Harrisburg. About seventy more live as servants in the homes of white employers. (learn more)

1821 Harrisburg passes an ordinance to regulate the movement and track the residence of all free African American persons in the borough.

1825 Harrisburg tax records show six African American property holders.

1825, April Harrisburg's first reported incident in which local Blacks come to the aid of a captured fugitive slave with the use of public demonstration and force in an unsuccessful rescue attempt.

1825 Jane Marie Morris escapes to York from a slaveholder in Baltimore, and comes to Harrisburg later that year. She is married to George Chester by the Rev. William R. DeWitt in 1826.

The Scriptures are fulfilled as spoken of by the Prophet Joel, Chap. 27th, 2nd verse. "Ye shall know that I am in the midst of Israel, and that I am the Lord, your God, and none else, and my people shall never be ashamed. And it shall come to pass afterwards, that I will pour out my spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall Prophecy. Your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions." In 1831, a young man who professed to be righteous, says he saw in the sky men, marching like armies, whether it was with the naked eye, or a Vision by the eye of Faith, I cannot tell. But the wickedness of the people certainly calls for the lowering Judgments of God to be let loose upon the Nation and Slavery, that wretched system that eminated [sic] from the bottomless pit, is one of the greatest curses to any Nation.

(Jarena Lee, Religious Experience and Journal of Mrs. Jarena Lee, Giving an Account of Her Call to Preach the Gospel, Revised and corrected from the Original Manuscript, written by herself, Philadelphia, 1849, pages 41-42; electronic version: "Lee: Religious Experience and Journal." Microsoft Encarta Africana Third Edition. 1998-2000 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.)

1829 Wesley Union AME church is founded in a log building at Third and Mulberry Streets by members of the African Church. It's membership rises to 115 within a year. (learn more)

1830 Federal census schedules show at least 85 identifiable free Black families in Harrisburg, totaling over 500 persons. Many now own their own homes.

1830 Family lore says that the Rutherford family was actively helping fugitive slaves throughout this time period from their farms in Swatara Township.

Garrisonian Anti-Slavery, 1831-1839

1831, October An anti-colonization meeting is called at the Wesley A.M.E. Church at Third and Mulberry Streets, in the neighborhood of Judystown. Pastor Jacob Richardson chairs the meeting and helped guide the resolutions, which were published in The Liberator. At this same meeting, George Chester was appointed Harrisburg agent for Garrison's newspaper. (Learn more)

1831-1834 The oyster house and restaurant of George and Jane Chester, located in the cellar at Third and Market Streets, sells Garrison's Liberator newspaper, and becomes "a hub of local abolitionist activity." (R.J.M. Blackett, Thomas Morris Chester: Black Civil War Correspondent [Baton Rouge, 1989] p. 5; The Liberator, October 8, 1831)

1832, November In an editorial that is reproduced in Garrison's The Liberator, the editor of the York Farmer newspaper explains why he refused to print an advertisement seeking the return of a runaway named Sarah, predicting "The time is approaching, when no Pennsylvania editor will be found willing to act as an assistant in the noble work of detecting and recapturing a fugitive slave." (The Liberator, 17 November, 1832)

1833, June Harrisburg sends two delegates to the Annual Convention of People of Color, held in Philadelphia. The aims of the convention include the improvement of the condition of African Americans in the north and opposition to colonization. (The Liberator, 15 June, 1833)

1834, October 24 James Williams, an African American living near Middletown with his wife and four children, is arrested on a warrant and taken to Hummelstown. He is held until evening and released for lack of evidence, but upon returning home finds his wife and children gone and his home ransacked. Believing them kidnapped, Williams enlists the help of George Fisher of the local abolition society. The kidnappers and their captives are traced as far as York, where Williams finds his wife, who had escaped. A posse is formed the following day to track down the kidnappers and children, which they do. A trial for four of the men involved in the kidnapping plot is held at Harrisburg in January, 1835. At the conclusion of the weeklong trial, Theophilus Hughes, William Hyde, Asa Smith and William H. Fresh are all convicted of conspiracy and false imprisonment, and Hyde is further convicted of assault with a loaded pistol. All were fined and imprisoned at Harrisburg. (The Liberator, April 25, 1835)

1835, late December Alexander Graydon hosts Harrisburg's first anti-slavery lecture in his parlor. His speaker, an agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society, is an elderly Quaker gentleman from Philadelphia, Samuel L. Gould, who lectures on the history of anti-slavery and concludes with a plea for action. The meeting is thinly attended. Gould also spoke at the Wesley Church on January 1, 1836. (The Liberator, 13 February 1836) (also see 1836, January 1 and 1837, July, below)

1836, January 1 American Anti-Slavery Society lecturer Samuel L. Gould speaks at the Wesley Church in Judystown, addressing a mostly African American audience. His series of anti-slavery speeches inflames the local town council, which, fearing he is "exciting the colored population of this borough," issues an official resolution calling for him to "desist from his efforts." (The Liberator, 13 February 1836)

1836, January 14 Harrisburg Anti Slavery Society is formed. It's president is Rev. Nathan Stem, an Episcopal minister. Among Harrisburg's clergy, only Rev. John Winebrenner, a manager of the new society and later its corresponding secretary, and Rev. Stem openly oppose slavery. Winebrenner's Gospel Publisher begins to print anti-slavery articles and is subsequently burned on the streets of Richmond by angry southerners. (George Ross, Biography Of Elder John Winebrenner, 1880, Harrisburg, PA, p. 20.)

1836, October 25 Jonathan Blanchard arrives in Harrisburg as a new agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society and spends a little over a week giving anti-slavery lectures. His first lecture in Market Street Presbyterian Church provokes considerable opposition. He lectured on November 2nd in Dauphin, November 3rd in Halifax and spoke in Millersburg on November 4th. (John L. Myers, "The Early Antislavery Agency system in Pennsylvania, 1833-1837, Pennsylvania History XXXI [January 1964], 78.)

1836, December 3 The Adams County Anti-Slavery Society is formed at Michael Clarkson's Academy after having been forced from the county court house in Gettysburg by an anti-abolitionist mob. Founding members include James McAllister, Robert Middleton, Michael Clarkson, William Wright, Joel Wierman and Professor William M. Reynolds. (G. Craig Caba, Gettysburg: 1836 Battle Over Slavery, 2004, n.p. [5-8])

1837 Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society formed in Harrisburg. Its members include Robert Purvis, Lucretia Mott and James Miller McKim (Carlisle abolitionist). (See 1837, January 31-February 2, below)

1837, January While serving as a state legislator from Adams County, Thaddeus Stevens meets abolitionist lecturer Jonathan Blanchard in Harrisburg. Stevens, already leaning toward anti-slavery views, invites Blanchard to dinner in Gettysburg and contributes $90 toward the cause. Stevens and Blanchard become lifelong friends, and Blanchard is considered to be a strong influence in Stevens' commitment to the cause of radical anti-slavery. In time, Stevens will become the most influential voice of abolition in the United States Congress.

1837, January 31 - February 2 First convention in Pennsylvania of the American Anti-Slavery Society. This is an organizational convention, in which the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society is formed. Attendees include Dr. F. Julius LeMoyne, Charles C. Burleigh, Jonathan Blanchard, Benjamin Lundy. Proceedings were reported to The Liberator by correspondent John Greenleaf Whittier. (The Liberator, Feb. 11, 18, 1837)

1837, 24 February An anti-abolition meeting in Susquehanna Township elects trustees to manage the Hailman Schoolhouse in the township. The citizens charge the trustees with allowing the use of the schoolhouse for preaching, "but in no event shall they open the door to lectures on abolitionism, negroism, and amalgamationism." ("Refuge of Oppression. Anti-Abolition Meeting," The Liberator, 18 March 1837)

1837, May As a delegate to the state constitutional convention in Harrisburg, Thaddeus Stevens frustrates several attempts to place anti-Black provisions in the new constitution, proposes laws to protect the rights of fugitive slaves, and delivers a powerful anti-slavery speech. He is unsuccessful, though, in blocking the denial of suffrage to Blacks, and refuses to sign the final document.

1837, July Alexander Graydon advertises a list of 29 different "Anti-Slavery Publications" for sale at his store on Market Street, "Together with sundry pamphlets, prints &c." Graydon's stock includes Picture of Slavery in the United States, with plates, by George Bourne, for 50 cents, and Memoirs & Poems of Phillis Wheatley for 37 cents. Graydon is shunned by the Presbyterian church for his abolitionist crusade and eventually moves to Indianapolis. (Pennsylvania Telegraph [Harrisburg], July 27, 1837) (learn more)

1837, September Writing from Columbia, Pennsylvania, anti-slavery advocate and African American intellectual William Whipper advocates the use of non-resistance as the only means consistent with human reason to combat the evils of slavery. His address "On Non-Resistance to Offensive Aggression" shows how abolitionists struggled with the question of how best to fight for the end of slavery. (learn more)

1837, December Writing in the Gospel Publisher, Jonathan Blanchard notes "An Anti-Slavery Society was formed in Middletown, Dauphin County, the day before yesterday." Blanchard goes on to urge local residents to become active in the cause of anti-slavery. (Gospel Publisher, 2 December, 1837)

1838, January The second annual convention of state anti-slavery agencies is held in Harrisburg. Held in Shakespeare Hall, at the corner of Locust and Court Streets, it attracted several hundred delegates, male and female, black and white, from across the state. They listened to speeches from Dr. F. Julius LeMoyne and William Burleigh, among others. (Harrisburg Telegraph, 17 January, 1838)

1838, January 28 Anti-slavery lecturer William H. Burleigh is in Harrisburg as part of a lecture tour through Pennsylvania. Burleigh had attended a lecture by Dr. Booth of the Pennsylvania Colonization Society, held at a local church, on January 28th, and in a letter to The Liberator, denounced Booth as a "pro-slavery man" promoting colonization. (The Liberator, 23 February 1838)

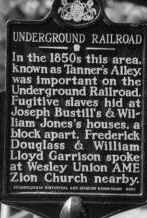

1839 Wesley Union A.M.E. moves to the corner of South Street and Tanner's Alley. It becomes increasingly active in sheltering, feeding and clothing fugitive slaves. Bethel A.M.E., on Short Street, is also said to have been active in Underground Railroad activities.

1839, June 27 Two men arrive at the offices of the Vigilant Committee, in Philadelphia, one of whom is a fugitive slave sent from Columbia by Underground Railroad agent William Whipper. The case record notes that he was sent to "Morrisville [Bucks County], thence to N.Y. for Canada." ("Record of Cases Attended to for the Vigilant Committee of Philadelphia by the Agent," published in "The Vigilant Committee of Philadelphia," Joseph A. Borome, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 92 (January 1968), p. 331.)

1839--summer New York clergyman-abolitionist Charles B. Ray visits York, Harrisburg, Carlisle, Chambersburg and Pittsburgh on his Pennsylvania Tour, sponsored by The Colored American newspaper. He was disappointed by the response of Harrisburg's African American community to his visit, noting "I staid here but two nights, and had a meeting of our own people on each, lectured once, and preached once, and procured but ten subscribers among a population of some hundreds. How is this?" Although he did not find subscribers, he did find support, writing "There are however a few choice spirits here and most of them either had, or did subscribe for the paper, I found a few very choice white abolitionists, some of whom rendered the paper some assistance." ("Pennsylvania, No. 2," in The Colored American [New York], 31 August 1839.)

The Underground Railroad Network Develops, 1840-1849

1840

Harrisburg abolitionist and member of a local Underground Railrod family, Dr. William W. Rutherford, subscribes to William Lloyd Garrison's anti-slavery publication The Liberator.

(Learn More)

1842 State historian Frederic A. Godcharles recorded that in 1842 Harrisburg, a "great mob of Negroes" attacked some slave catchers with clubs and stones. (Chronicles of Central Pennsylvania [New York, 1944], 146)

1842, November 24 A Harrisburg constable leads a group of Maryland slave catchers and an assembled mob of local white residents to the home of William M. and Mary Jones, at River and Barberry Streets, in search of hidden fugitive slaves. When Jones refused them admittance, the constable broke down their door with an axe and allowed the assembled mob and the slave catchers to enter their home. No fugitive slaves were found. Jones had the constable and two of the slave catchers arrested and in a hearing, was successful in having the slave catchers charged and held to bail. Read more about this incident here.

1843, July The Baltimore Sun carries a story of one Mr. Ridgely, of the Baltimore investigative firm Hays, Zell, and Ridgely, who traveled to Harrisburg to arrest Archibald Smith. Smith was a free African American from Baltimore who was accused of aiding in the escape of slaves from the plantation of Richard Emery, of Baltimore County. Ridgely returned to Baltimore with Smith in custody on July 19. Nine years later Ridgely would be the key figure in the fatal shooting of fugitive slave William Smith, in Columbia, PA. (The Sun [Baltimore, MD], July 20, 1843)

1843, Summer The twelve escaped slaves who were being piloted by Archibald Smith, who was arrested in Harrisburg (see above) get lost near Emmitsburg, Maryland, but manage to get very near to Gettysburg before a posse of slave catchers finds them. The fugitives successfully defend themselves and make it to Harrisburg, where ten of the twelve are captured after putting up resistance in a barn not far from town. (The Liberator, 01 December 1843)

1844, December 3 Underground Railroad activist Charles T. Torrey is convicted of aiding fugitive slaves escape from Maryland into Pennsylvania. He was sentenced to six years in the Maryland Penitentiary, where he died in May 1846 of tuberculosis. (Archives of Maryland, "Charles T. Torrey," www.msa.md.gov/)

1845, January Two men, Alexander A. Cook and Thomas Finnegan, attempt to kidnap Harrisburg resident Peter Hawkins. Cook and Finnegan assaulted Hawkins in broad daylight, bound him and attempted to leave town with him on the pretext of returning him as a fugitive slave. Several residents stopped them, and the matter was referred to Dauphin County Judge Nathaniel Bailey Eldred. Judge Eldred released Hawkins and charged Cook and Finnegan with kidnapping. (Carlisle Herald & Expositor, 29 January 1845; The Liberator, 14 February 1845)

1845, April 2-3 A delegation of American Antislavery Society speakers, including Abby Kelley (later Abby Kelly Foster) and Jane Elizabeth Hitchcock, speak at the Courthouse in Harrisburg. A Philadelphia correspondent reports that they lectured to large audiences, "many of whom were ladies." Unfortunately the lectures were marred by pro-slavery activists who "raised false alarms of fire," heckled the speakers, and showered the group with eggs. The women were also threatened with tar and feathers, and duckings. ("Mobocracy in Harrisburg," Carlisle Herald & Expositor, 9 April 1845; "Mobocratic Interruptions," The Liberator, 25 April 1845)

1845, July 24 The Kitty Payne family, consisting of a mother and three children who were manumitted in Maryland and relocated to northern Adams County, was kidnapped by a gang led by Thomas Finnegan, and taken to reenslavement in Maryland. Finnegan was eventually captured on a subsequent foray into Adams County and tried, found guilty, and sentenced to five years at Eastern Penitentiary. The Payne family was eventually able to return to Adams County. (Read the original news account of this incident in the Carlisle Herald & Expositor, of 6 August 1845)

1845, August 1 Emancipation Day in Carlisle. From the Carlisle Herald: "The colored people of this borough celebrated the Anniversary of British Abolition of Slavery in the West Indies, on the 1st instant, in a Grove adjacent to town, where they listened to several addresses from some of their own number. In the evening they returned to town, both sexes marching in procession and singing as they passed through the several streets." (Carlisle Herald and Expositor, 6 August 1845).

1845, October A large party of ten fugitive slaves shows up at the door of Samuel Rutherford in Swatara Township. Some are captured when a group of slave catchers shows up. This is the most oft-related incident in Harrisburg UGRR history. At this point in time, fugitives are sent north from Harrisburg. The Rutherford family favors sending fugitives to Wilkes-Barre by way of Linglestown, Harper's Tavern, Lickdale, and Pottsville. Others are sent from Harrisburg north along the river to Selinsgrove and Williamsport, then to Elmira.

1846, December The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society held its annual Anti-Slavery Bazaar in the week before Christmas. Among those publicly acknowledged who made "generous contributions" were persons from Harrisburg. (The Liberator, 29 January 1847)

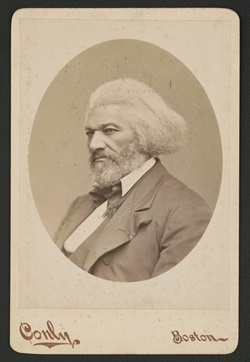

1847, July 20 A delegation of citizens meets in the A.M.E. church to propose inviting William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass to Harrisburg. John F. Williams, Thomas Early and Edward Bennett drafted resolutions to welcome Garrison and Douglass, and to prepare arrangements and accommodations for them while in Harrisburg.

1847

Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison deliver

anti-slavery lectures in Harrisburg at the invitation of

William W. Rutherford. The appearance is marred by mob

violence.

(Read a detailed account of this event here.)

1848, December 13-14 Harrisburg's African American community hosts an informal state convention to actively campaign to regain the vote for Black men in the commonwealth. Among those in attendance on the floor of the convention, held at Shakespeare Hall, are Charles Lenox Remond, Martin Delany, Robert Purvis, Stephen Smith, Abraham Shadd, John B. Vashon, Rev. Mifflin Gibbs and John Peck Following the convention, Purvis and Vashon led a delegation to present the Harrisburg Resolutions to Gov. William F. Johnston. Despite a dynamic start that included plans for a state organization, a political newspaper, traveling lecturers, petition drives and more, the effort fizzled after several months. (The North Star, January 5, 1849, June 22, 1849)

1848, March Female abolitionist Abby Kelley Foster lectures in Harrisburg. This is her second appearance in Harrisburg (see 1845, April). Foster, a forceful and dynamic speaker, convinced many women that they could have an active, vocal role in social change. The Philadelphia U.S. Gazette belittled Foster's Harrisburg appearance by noting "We wonder if she knows how to broil a steak or knit stockings." (learn more)

1849, August 10 Abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond lectures in Harrisburg. (The North Star, August 3, 1849)

1849, September Harrisburg Blacks successfully rescue a family of five from slave catchers, hide them in their homes on Short Street and set up a neighborhood watch to guard them. Sheriff Jacob Shell scatters the watch with an impromptu marshaling of a local militia company.

Active Resistance and High Activity, 1850-1865

1850, August Harrisburg constable Solomon Snyder arrests three fugitive slaves and begins Harrisburg's most notorious fugitive slave incident. Harrisburg Blacks respond with violence and several persons are injured, including Joseph Popel, whose heroic charge into the crowd of slave catchers allows one fugitive to escape. The local militia is called out and quells the crowd by rolling cannons into place on Walnut Street. This also marks the beginning of the legal arrangement between Harrisburg's Black community and lawyers Mordecai McKinney and Charles C. Rawn to represent fugitive slaves at hearings. (learn more)

1850, September Richard McAllister is appointed Federal Slave Commissioner to hear cases against fugitives as a result of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. His first case involves remanding south the slaves still held in the August 1850 riot.

1850, October Two women are seized in Harrisburg by slave catchers, but McAllister is forced to set the women free when they prove their free status. The American Anti-Slavery Society, based in New York, reports that in this month a "number not stated were brought before Commissioner M'Allister, when 'the property was proven, and they were delivered to their masters, who took them back to Virginia, by railroad, without molestation.' " (The Fugitive Slave Law and its Victims, 1856, New York)

1850, November McAllister issues a warrant for four fugitives in Harrisburg and sends them to the Baltimore claimant without a hearing. This is the first of several incidents that throw doubt on McAllister's character.

1851, January McAllister remands a local man, David, to Virginia.

1851, April The Franklin family is arrested in Harrisburg, including a small child born in Pennsylvania. McAllister tries to suppress protests by holding the hearing in the pre-dawn hours, but word gets out. The family is sent south without the youngest child, who is placed with a local Black family.

1851, August Bob Sterling is remanded south by McAllister.

1851, October 2 During the night of Thursday, October 2, John Dunmore is arrested and taken before Richard McAllister and accused of being a runaway slave. The hearing was conducted behind closed doors and windows in McAllister's office. However the person who was seeking his return testified that Dunmore was not his slave, and Dunmore is released. (Harrisburg American, as reported in the Frederick Douglass Paper, October 9, 1851. A slightly different version of this same story was reported in The Liberator, 17 October 1851, citing a letter from a Harrisburg correspondent.)

1851, October After Harrisburg District Judge John J. Pearson dismisses charges against four men accused of having participated in the Christiana Riots, Commissioner McAllister immediately seizes the men in the courtroom and remands them south after a short hearing.

1851, November A man named Henry, accused of being the fugitive slave of a Dr. Duvall, of Prince George's County, Maryland, is remanded south after being seized in Columbia. (American Anti-Slavery Society, The Fugitive Slave Law, and Its Victims, 1856)

1851, November Two men are arrested at Columbia on the warrant of Commissioner McAllister, accused of being fugitives belonging to W. T. McDermott, of Baltimore. One of the accused men escapes, but the other is remanded south. (American Anti-Slavery Society, The Fugitive Slave Law, and Its Victims, 1856)

1851, December William Kelly, captured in Lycoming County, is remanded south following a hearing in the middle of the night. (Pennsylvania Freeman, reported in the Frederick Douglass Paper, December 25, 1851)

1852, March Acting on a warrant from Commissioner McAllister, Solomon Snyder accompanies Baltimore policeman Ridgeley to Columbia to arrest alleged fugitive William Smith. When Smith resists capture, Ridgeley shoots him to death. The incident sparks outrage in the north but Ridgeley is never brought to trial.

1852, June James Phillips, a longtime Harrisburg resident, is sent south, causing an uproar not only in Harrisburg's Black community, but with whites as well. Attorney Rawn is dispatched to Richmond with $800 to buy Phillips' freedom.

1853, March In political fallout from his increasingly unpopular pro-slavery activities, all three elected constables who helped Commissioner McAllister capture fugitive slaves in Harrisburg are turned out of office. McAllister resigns his post a short time thereafter. The number of fugitive slaves captured in Harrisburg after this date drops sharply.

1854, June 12 With Richard McAllister out of the picture (see 1853, March, above), slave holders are forced to go to Commissioner E. D. Ingraham in Philadelphia for warrants. On June 12, three men from Maryland, accompanied by a Philadelphia marshal, arrived in Harrisburg in search of a fugitive who was working in a brick-yard in town. The hunted man was spirited out of town by local Underground Railroad activists before he could be located by the slave catchers. (Reported in the Provincial Freeman [Toronto], July 1, 1854)

1854, August 01 On behalf of the citizens of Harrisburg, Senator James Cooper (Whig, Pennsylvania) presents a petition to the U.S. Senate "praying the repeal of the fugitive slave law." The petition was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary. (Journal of the Senate, August 1, 1854, p. 620)

1854, August 31 William James Watkins, Associate Editor of The Frederick Douglass Paper, and eloquent African American speaker, lectures in Harrisburg.

1854, September Henry Massy is arrested in Harrisburg and taken before U.S. Slave Commissioner E. D. Ingraham at Philadelphia as the alleged property of Franklin Bright, of Queen Anne's County, Maryland. (Reported in The National Era [Washington, DC], October 5, 1854)

1855, January A large fire sweeps through parts of Judystown, destroying several frame houses and causes havoc with the Underground Railroad operations of Edward Bennett, who is still actively concealing fugitives at this point. (Egle, Notes and Queries, Annual Volume 1900, XII, p. 63)

1855,

February Solomon Snyder oversteps his

bounds when he tries to kidnap a local African American youth,

George Clark, by luring him into a hotel room where

accomplices lay in wait to overpower the boy. Clark's

screams bring help and Snyder is arrested and ultimately

imprisoned. Snyder's arrest was reported in the Baltimore Sun:

ALLEGED ATTEMPT TO KIDNAP. -- Sol. Snyder, white, and David Jackson, colored, have been arrested at Harrisburg, Pa., on the charge of attempting to kidnap a colored boy named George Clark. James Thompson, colored, also implicated, made his escape. (The Baltimore Sun, 28 February 1855, page 1.)

1855, June Henry Cromwell escapes from Baltimore to Harrisburg and rides directly to Philadelphia on a freight train. It is not known who assisted him in Harrisburg.

1855, December Robert Brown, of Martinsburg, Virginia, arrives in Harrisburg during the last week of December, cold and hungry, bearing no supplies or possessions other than an image and locks of hair from the family that was sold away from him a few weeks earlier. He is taken in and forwarded to Philadelphia, arriving there late on New Years Day, 1857. (William Still, The Underground Rail Road, p. 121-122)

1856, January Joseph C. Bustill begins operation in Harrisburg, forming the Harrisburg Fugitive Aid Society. Some of his correspondence with William Still is preserved. Bustill begins the method of sending fugitives to Reading or Philadelphia by train. One of his first operation consists of a group of eight fugitives. Not all fugitives are sent directly north after this.

1856, May A busy month for Bustill in Harrisburg. Among those he sends to Philadelphia are a fugitive posing as the slave of a white woman and her small child, and six fugitives from Maryland.

1856, June 12 One of two women who arrived on this day at the offices of William Still in Philadelphia is Jane Johnson. In his notes, Still records that Johnson "when in Harrisburg went by the name of Jane Wellington," and that she "was owned by David Beiller...who lived near Hagerstown." (Still Journal, Volume C, page 285, Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

1857 Bustill begins regularly utilizing the telegraph to alert William Still of arriving fugitives.

1857, May Bustill sends four fugitives to Reading, where they are detained due to the presence of slave catchers. Bustill holds three more fugitives until the situation becomes safer. The Reading agent occasionally sends fugitives directly to Elmira, where possible.

1857, May David Cooper, claimed to be a runaway slave "of bad habits" belonging to Margaret Booth of Washington County, Maryland, is captured in Harrisburg. Booth petitions the Maryland courts, presenting a bill of costs from Baltimore slave traders Wilson and Hindes, to sell Cooper out of state. The court consents to the sale. (Maryland State Archives, "Washington County Register of Wills (Petitions and Orders)" [MSA T450-1] "Margaret Booth vs. David Cooper Negro Slave")

1857, May Two men, John Sanders and Thomas Nathans, are convicted and sentenced to five years at hard labor in the Dauphin County prison for attempting to kidnap Harrisburg free Black resident Jerry Logan. (The Compiler [Gettysburg, PA], 18 May 1857)

1857, June 8 Colonization Lecture: "Lecture on Liberia--Dr. R. W. Morgan, Missionary to Liberia, will lecture in the Masonic Hall, Tanner's alley, this evening, at 7 o'clock. Admittance 12 cents. Subject, Liberia. From the well known ability and reputation of this gentleman, a rich treat may be expected." (Harrisburg Daily Herald, June 8, 1857)

1857, December 17 Jacob Dupen, an accused fugitive slave from Baltimore, is arrested while plowing a field "about four miles from Harrisburg." The Philadelphia Bulletin reported that Dupen, age thirty, was the property of William M. Edelin, of Baltimore, and that he had a wife and four children in Baltimore County. The newspaper reported that, in the hearing before Philadelphia judge Kane, "There was no excitement about the Court room; indeed there was no one present except the officers of the Court and the parties." (Philadelphia Bulletin, December 18, 1857 and reprinted in the New York Times, December 21, 1857)

1858 An unnamed fugitive slave is buried on the mountain north of Linglestown, apparently having committed suicide when faced with capture. He is one of the few fugitives who traveled directly north from Harrisburg during this time period.

1858, April 8 William Simms and three fellow freedom seekers arrive in Harrisburg from Carlisle, having escaped from Chestnut Hill Farm near Leesburg, Virginia. Simms and his three companions had not entered Carlisle, but had gone around the town, while two additional companions had entered Carlisle and had become separated from the group. The four men, including Simms, who entered Harrisburg, are recognized as fugitive slaves and chased, eventually fleeing north along the Susquehanna River. Eventually Simms, by now alone, would reach Ithaca, New York, where he established himself as a tenant farmer.

On his entire journey from Virginia to New York, Simms does not appear to have encountered any Underground Railroad assistance, although several of his companions, after becoming separated from him, did, and also reached New York. (learn more)

1859, April Daniel Dangerfield, formerly enslaved as a helper at Aldie Mill, Loudoun County, Virginia, and who escaped in 1853, is arrested in Harrisburg's market square and taken to Philadelphia for a hearing. He had been living for several years with the Rutherford family in Swatara Township and had a wife in the city. He is subsequently released, having been supported through the hearing by large, boisterous crowds of African American citizens and prominent Philadelphia area abolitionists, including Lucretia Mott. (Dangerfield's enslavement and escape in Virginia is documented at "A Chronology of Important African American Events in Loudoun County Virginia" by the Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia, 2004, researched by Eugene M. Scheel [http://www.balchfriends.org/Glimpse/chronology.htm], accessed August 19, 2004; An account of the crowds at the hearing is contained in a letter from Martha Coffin Wright to David Wright, April 7, 1859, Garrison Family Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, and printed online at http://womhist.binghamton.edu/mcw/doc3.htm accessed July 1, 2005).

1859, August 1 Emancipation Day in Harrisburg is celebrated with speeches, including a notable oration by Jacob C. White, who asked why Black men have "No rights in a land which embosoms the hallowed remains of our ancestors? No liberty in a country which was freed by our own arms?" (Weekly Anglo-African, 13 August 1859)

1859, November Dr. William W. Rutherford is involved with planning the escape of several of John Brown's raiders through Pennsylvania, including Brown's son, Owen Brown. (Judge Alexander K. McClure to J. Howard Wert, 10 December 1904, reproduced in Caba, Episodes of Gettysburg and the Underground Railroad, 1998, p. 112)

1859, December J. Howard Wert, as a member of the Beta Delta fraternity of Pennsylvania College, Gettysburg, aids in hiding a fugitive slave in a fraternity hideout on Culp's Hill, then forwarding him to Quakers in York Springs, who presumably send him on to Harrisburg. (J. Howard Wert, "Recollections of the Underground Railroad," in Caba, Episodes of Gettysburg and the Underground Railroad, 1998, p. 72-77.)

1860, January - February The Beta Delta fraternity of Pennsylvania College becomes an active part of the Adams County-to-Harrisburg Underground Railroad network. The Black Ducks are the link between the African American community and the white Quaker activists of York Springs. (J. Howard Wert, "Recollections of the Underground Railroad," in Caba, Episodes of Gettysburg and the Underground Railroad, 1998, p. 76-77.)

1860,

March Moses Horner is captured by slave

hunters, including Deputy U.S. Marshal Jenkins, near

Harrisburg and taken to Middletown, where the party catches a

train to Philadelphia to have the man examined by Judge John

Cadwalader of the U.S. District Court as a fugitive

slave. A rescue attempt by a multi-racial crowd of

anti-slavery activists is attempted, but fails, drawing

national attention. Abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins

Harper writes to the Weekly Anglo-African in praise of

the rescue effort and calls for national action, saying "Shall

these men throw themselves across the track of the general

government and be crushed by that monstrous Juggernaut of

organized villainy, the Fugitive Slave Law, and we sit silent,

with our hands folded, in selfish inactivity?" Horner is

ultimately remanded into slavery by the judge. (Pennsylvania

Telegraph, March 4, 1860; Harper's quote is excerpted in

Klein, Sarah. Me, You, the Wide World: Letters & Women s

Activism in Nineteenth Century America . Women Writers: A

Zine. Editor, Kim Wells. Online Journal. Published: May 16,

2001 Available at:

<http://www.womenwriters.net/may2001/zineepistolary.htm

>. August 25, 2005.)

1861, late May Fugitive slaves begin appearing on the streets of Harrisburg in large numbers. Telegraph editor George Bergner, who has connections with local African American Underground Railroad operatives, notes "We are informed by those who have opportunities of knowing, that since the commencement of the rebellion, hundreds of southern 'chattels' have passed through this city en route to the north." ("Fugitives From the South," Pennsylvania Daily Telegraph, 1 June 1861)

1861, late June A local African American boy named Dorsey returns to Harrisburg after a harrowing experience in New Orleans. As the Telegraph reported "Dorsey went to 'Dixie's land,' as an employee on a steamboat, was captured in New Orleans and thrust into prison, where he remained for several days. Through the instrumentality of the captain he finally regained his liberty, after paying a heavy fine, and made his way home, arriving here a day or two ago." (Pennsylvania Daily Telegraph, 28 June 1861)

1861-1865 Fugitive slaves arrive in Harrisburg by traveling with Union troops. One such person is George Washington, who came north with the Ninth Pennsylvania Cavalry during the war. He is buried in Paxton Presbyterian Cemetery. During this time the UGRR activity of Dr. William W. Rutherford ceases as he serves as a regimental surgeon during the war.

1862, April Longtime Anti-slavery speaker Wendell Phillips spoke to a large crowd at Brant's Hall in Harrisburg, in response to Democratic charges that abolitionists and anti-slavery policies were to blame for the bloodshed and destruction of the war. Phillips laid blame for the war on the institution of slavery, noting that its "doom was proclaimed in its own position; and its end, with the fearful enormities of which it had been the author, would go down into darkness and disgrace." Before his appearance, the audience was warmed up by the nationally known anti-slavery singers The Hutchinson Family, whose repertoire now included many patriotic songs. (The Liberator, 4 April 1862)

1863, April The Harrisburg Daily Telegraph reports on a fugitive slave who was being lawfully taken through the city back to slavery in Maryland. (learn more)

1863, late June As the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia sweeps into Pennsylvania's lower counties, Harrisburg is inundated with African American refugees from the Cumberland Valley. Most cross the Susquehanna River on the Camelback Bridge and encamp at the riverfront near Market Street. The city scrambles to feed and care for this huge influx of people that includes free Blacks and fugitive slaves. Many of the able-bodied men are enlisted to help build the fortifications in Fort Washington and Fort Couch.

1864, June 28 The Fugitive Slave Act is repealed by Congress.

Post-War Events

1876 William Whipper, prominent spokesman for abolition, anti-slavery and African American rights, dies in Philadelphia. (learn more)

Now Back in Print with New Cover Art

The Year of Jubilee

Vol. 1: Men of God and Vol. 2: Men of Muscle

by George F. Nagle

Both volumes of the Afrolumens book are back in print and may be ordered from Amazon.

Both volumes of the Afrolumens book are back in print and may be ordered from Amazon.

The Year of Jubilee is the story of Harrisburg's free African American community, from the era of colonialism and enslavement to hard-won freedom.

Volume One, Men of God, covers the turbulent beginnings of this community, from Hercules and the first enslaved persons, the growth of slavery in central Pennsylvania, the Harrisburg area slaveholding plantations, early runaway slaves, to the birth of a free Black community. Men of God is a detailed history of Harrisburg's first Black entrepreneurs, the early Black churches, the first Black neighborhoods, and the maturing of the social institutions that supported this vibrant community.

It includes an extensive examination of state and federal laws governing slave ownership and the recovery of runaway slaves, the growth of the colonization movement, anti-colonization efforts, anti-slavery, abolitionism and radical abolitionism. It concludes with the complex relationship between Harrisburg's Black and white abolitionists, and details the efforts and activities of each group as they worked separately at first, then learned to cooperate in fighting against slavery. Digital version available here

Non-fiction, history. 607 pages, softcover.

Volume Two, Men of Muscle takes the story from 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Law of

1850, through the explosive 1850s to the coming of Civil War to

central Pennsylvania. In this volume, Harrisburg's African

American community weathers kidnappings, raids, riots, plots,

murders, intimidation, and the coming of war. Caught between

hostile Union soldiers and deadly Confederate soldiers, they

ultimately had to choose between fleeing or fighting. This is

the story of that choice.

Volume Two, Men of Muscle takes the story from 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Law of

1850, through the explosive 1850s to the coming of Civil War to

central Pennsylvania. In this volume, Harrisburg's African

American community weathers kidnappings, raids, riots, plots,

murders, intimidation, and the coming of war. Caught between

hostile Union soldiers and deadly Confederate soldiers, they

ultimately had to choose between fleeing or fighting. This is

the story of that choice.

Non-fiction, history. 630 pages, softcover.