a book about Harrisburg...

by George F. Nagle

Other Study Areas:

Chapter Seven

Rebellion

For the Down Trodden and Oppressed!

In the dead of night, sometime about 1835, young Mary Ellen Graydon was awakened from her sleep by some commotion in her household, and "a peculiar call." The noise, and the events that she witnessed that night, so impressed the young girl that she could vividly recall the details many years later as she recorded them in her published memoirs for her own children.

As the oldest daughter of busy Harrisburg hardware merchant Alexander Graydon and his wife Jane, twelve-year-old Mary Ellen probably shared her bedroom on an upper floor of the family's Market Street home with some of her younger siblings. Although the house was long and narrow and had many rooms, typical of the residences along the town's main streets that housed both a business on the ground floor and living space above, the family was large and every room was put to maximum use. Adjoining the family home was her father's mercantile business, located in a prime spot along the fast developing street, on the southeast corner of Market Street and Court Alley, directly across the street from the county courthouse.

It is perhaps ironic that the scene that imprinted itself that night in the memory of Mary Ellen was an act of bold defiance against the laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the United States, yet it occurred under cover of darkness within yards of the seat of justice in the County of Dauphin. On that night, Mary Ellen Graydon observed her parents secretly helping a group of fugitive slaves escape their pursuers.

Although she did not identify the year of her memory—it may have been a year or more earlier than 1835—the importance of the incident that she related is in the people involved and the location. The abolitionist views of Alexander and Jane Graydon were discussed earlier, but their roles as Underground Railroad operatives add an important link to understanding the development of how some white Harrisburg residents aided the cause of freedom seekers. Their daughter recalled that she awoke from sleep "to hear a peculiar call, then my father's step on the balcony, a hurried whisper, and later a group of dusky forms passing through my room, piloted by my mother to a secret hidden place."50 She mentioned that the fugitives were hidden and received the care of her mother "for many days," before being led to the next stop on their journey.

The role of Mary Ellen's mother, Jane Graydon, in leading the fugitives through the upper floor of the house, and in providing care for days on end, confirms that the family secreted fugitive slaves in their house in the second block of Market Street. The care provided would have gone well beyond the obvious need to feed these "poor souls." She would also have had to meet their basic sanitation needs, and provide washing, mending, sleeping arrangements, and perhaps even medical care. To do all this without arousing the curiosity of their neighbors required great planning, and it probably required that it be accomplished entirely within the walls of the family home and shop.

Mary Ellen Graydon does not mention taking any part in the care of these fugitives herself, but rather attributes all of their care to her mother, which probably means she and her siblings were too young to be directly involved. The additional work of caring for a group of strangers in her household—strangers who would have been highly dependent—while at the same time continuing to care for a number of young children, shows a high degree of dedication on the part of this woman. That dedication, however, was a hallmark of the Market Street home of Alexander and Jane Graydon.

There were, as mentioned, only a few like-minded white residents of Harrisburg at this time. Most of Harrisburg's white community viewed the enslavement of African Americans in the south as a matter of no concern. Those who did express concern for the rights of African Americans generally limited their involvement to agitating for the rights of free Pennsylvania blacks against southern kidnappers. Most saw fugitive slaves as fair game for recapture by their legal owners or their agents, and expressed strong disapproval when resistance to these capture attempts occurred, as happened on the street in front of the courthouse a few years earlier in 1825. At that time, local anger manifested itself in the swift sentencing of sixteen "rioters" to prison.

Such actions did not assuage the anxiety that Harrisburg's white majority felt toward its darker complexioned neighbors, however, which led to the popularity of the colonization movement as a means of solving the problem of how to deal with the increasing number of free African American residents. Harrisburg's white residents flocked to the colonization banner, giving new vigor to the organization that had organized in town in 1819, but until the 1830s saw limited support.

In Harrisburg, the African American community at first stood virtually alone in clear opposition to the colonizationists, declaring their intent to fight the movement as early as 1831 and finding public support only with such radical whites (and outsiders) as William Lloyd Garrison and Benjamin Lundy. The Rutherford family could be counted on to oppose colonization schemes, but their influence lay mostly in Swatara Township and the Paxton Presbyterian Church, outside of town. John Winebrenner and his followers were considered fringe elements yet, and his opposition to slavery was still seen by most Harrisburg whites as the ideas of an eccentric.

Only Alexander and Jane Graydon, and Alexander's brother Hugh Murray Graydon, stood out among Harrisburg's white community as clear opponents of colonization. Their links to the activist African American community were limited to a friendship with the Chester family, however, at least until Junius Morel arrived in town in 1835. Utilizing his rhetorical talents and organizational skills, Morel provided a spark that energized the local African American community into more unified action, and contacts that helped bridge the gap between them and the embattled white anti-slavery advocates.

Although Junius Morel did not bring the anti-colonization struggle to Harrisburg, his efforts did bring it into sharp focus here. It became the focus of intense debate between those who supported colonization, whether through the naïve belief that it was the only way to restore justice to an African American population robbed of its equity in the American dream, or through the racist fears that only removal of a rapidly breeding and unskilled population to the shores of Africa could forestall a race war in America, and those who opposed it as a misguided and harmfully paternalistic scheme at best, and a shockingly bold deportation attempt at worst. The debate raged in forums both public and private. Harrisburg residents read impassioned pleas in support of the American Colonization Society in their local newspapers, while well-meaning legislators introduced resolutions in the state Capitol calling for adoption of the goals of the ACS by the national government. The language of one particular resolution, sent to the United States Congress by Pennsylvania lawmakers on Christmas Eve 1829, must have sounded particularly bitter and cold to Harrisburg's African American residents in that season of supposed good will:

Whereas Pennsylvania is honorably distinguished in having led the way in benevolent efforts to improve the condition of the African race in this country…it seems, therefore, proper, than an association of enlightened and philanthropic men, who have united to form, for free persons of color, an Asylum in the land of their fathers, should receive the countenance and support of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania; …there is reason to hope that it may…offer a home and a country to all of these people who may choose to emigrate there; and their removal from among us would not only be beneficial to them, but highly auspicious to the best interests of our country.51

The implied threat in resolutions such as this one, couched in its "us" versus "them" language, and sinister references to the "best interests" of the country, was clear to free African Americans: leave the country or face the consequences. Harrisburg's black residents reacted appropriately, calling the entire plan "chimerical" and "preposterous," and accused local clergymen of intentionally misleading their congregations. Such efforts were the work of "false priests and prophets," they charged. In stark contrast to those who would "banish" them from their friends and homes, Harrisburg's African American community leaders praised those few who were speaking out against colonization, declaring, "We gratefully acknowledge the respect we entertain for those who have defended our cause—we mean our white friends."52

Such respect was born of the knowledge that pro-abolition stances taken by local whites were highly unpopular and socially disastrous. One of those who witnessed the chilling effect of social ostracism was Dr. Hiram Rutherford, the eighth child of William Rutherford, whose farm in Swatara Township was a reliable Underground Railroad station. Hiram, like his brothers John Parke, William Wilson, and Abner, was raised "to a thorough practical acquaintance with the labors of the farm," and, like the rest of his family, also received a well rounded education that culminated with his graduation from Jefferson Medical College, in Philadelphia.

Hiram also followed in the family tradition of opposing slavery, and he had many opportunities to observe the political climate in Harrisburg regarding the issue during the 1820s and 1830s. Rutherford wrote, "The anti-slavery Garrisonian crusade of the thirties had nothing sentimental in it. It was a direct slap in the face, as strong and stinging as the thesis of Luther. Conscious of its strength, slavery resented the attack and gathered its forces of State and Church to crush its daring opponent."53

Of the local anti-slavery activists, Rutherford singled out Alexander Graydon as the person most injured by the public backlash to his moral position. Graydon was an elder in the Presbyterian Church in the borough, and his wife and children were devout and loyal members. Trouble soon arose, however, when the anti-slavery views of Alexander and Jane came into conflict with the anti-abolitionist stance taken by most of the congregants.

Alexander's daughter, Mary Ellen, recalled one particular incident in which her father convinced the church pastor, Reverend William R. DeWitt, to allow noted abolitionist Jonathan Blanchard, who was staying in Harrisburg at the time, to be invited as a guest preacher. Reverend DeWitt strongly resisted the suggestion. As the head of a large and influential congregation—the First Presbyterian Church in Harrisburg counted as members most of the boroughs' movers and shakers—the pastor knew all too well how divisive the slavery issue could be, and he did not want to risk the appearance of favoritism. Alexander Graydon insisted, however, and promised the hesitant pastor "nothing but the plain gospel would be preached." DeWitt relented, trusting the word of his church elder that the pro-South congregation would not be offended by Blanchard's sermon, and arrangements were made to accommodate the guest preacher.

On the Sunday that Blanchard took to the pulpit in the old church building on the southeast corner of Second and Chestnut streets, however, he was greeted by a highly suspicious, even hostile congregation. He did not even get to finish his opening prayer before many of the faithful in the pews took offense at his words. Mary Ellen Graydon wrote that "Mr. Blanchard prayed 'for the sick and afflicted, for those shut up in cells of disgrace,' and horror of horrors! for 'the down trodden and oppressed!' " The last phrase was charged with political overtones, having been commonly used at this time by abolitionists to refer to slaves held in the Southern states. The effect of Blanchard's choice of words was immediate: "There was a sudden movement down the aisles, and slamming of pew doors . . .After this our good pastor studiously refrained from ever asking an abolitionist to preach."54

Alexander Graydon and his family paid a heavy price for their principled but highly unpopular stand, suffering not just social but spiritual ostracism as well. As his fellow abolitionist, Hiram Rutherford, painfully witnessed, the Graydon family was cut off from all of their familiar connections. Rutherford recalled, "A churchman by long habit and standing, he clung like a leech to its organization, only to receive the cold shoulder from the pastor, from the congregation and from his nearest relatives. It was a 'freeze-out,' public and private."

Graydon's daughter had only painful memories of what had once been joyful extended family gatherings, but which were reduced to "a source of dread" as family members, firmly divided over colonization versus abolition, argued bitterly. She was particularly troubled by the criticism of her father by her grandfather, William Graydon, who belittled his son's beliefs in front of her, calling them "wild ideas" and demanding to know "Why do you attempt to force public opinion. Why not let well enough alone?" Her father was not about to be cowed, even by the veteran lawyer, and held his ground, defiantly telling his father that he and his family would continue the struggle "until slavery is wiped out."55

Alexander Graydon was as good as his word, and his house and shop on Market Street soon became a hub for anti-slavery activity in the mid-1830s. Among the items he offered for sale was a line of anti-slavery books and pamphlets. Other than George Chester's oyster cellar, across the street, at which copies of William Lloyd Garrison's Liberator could be perused, this was the only establishment in Harrisburg to make such literature publicly available. Graydon took out advertisements in the local newspaper, the Pennsylvania Telegraph, to publicize his stock. Under the heading "Anti-Slavery Publications," he listed twenty-nine different titles, including The American Anti-Slavery Society's monthly publication The Anti-Slavery Record, at thirty-one cents, and Memoirs & Poems of Phillis Wheatley, at thirty-seven and one-half cents. In addition to these publications, he also carried "sundry pamphlets, prints and c." His daughter, Mary Ellen, wrote of the collections of persuasive material "I can well remember the piles of anti-slavery literature that found a place in our home."

Much of this was not kept for sale, but was to be distributed among the borough's residents, and oftentimes to be given to those who had even more influence: state legislators. Graydon and his small circle of anti-slavery advocates were self-appointed lobbyists for the cause, and took advantage of their proximity to state lawmakers to plead their case. Like Junius Morel, who relocated to Harrisburg for much the same purposes, Graydon and his friends took their arguments directly to the men who sat in the chambers of the state House and Senate. Unlike Morel, who undertook formal business-hour visits to discuss his point of view, Harrisburg's white abolitionists used a stealth approach, making late-night visits to the halls of the Capitol, during which time they left their literature on the desks of state congressmen.

This approach was necessary because visits from white abolitionists were barely tolerated. While African American visitors such as Morel might be politely received by lawmakers, the African American position was known and expected, and their political pull was negligible. Lawmakers could hear them out and then dismiss their requests without consequences. White abolitionists, on the other hand, were not so easily dismissed, and lawmakers found it easier to avoid them or refuse to see them in their offices. For that reason, Graydon and his accomplices found it was more expedient simply to leave the materials where the lawmakers would not fail to find them: at their desk in the Capitol. Again, Mary Ellen Graydon's reminiscences recall these episodes: "Many a time, at night, these good friends would carry them to the State House -- placing a pamphlet on every chair -- in both halls -- awaiting the perusal of its morning occupant. In the glare of day such a procedure would not be tolerated." Unfortunately, she does not hint at how Graydon and his associates circumvented the Capitol watchmen.56

In late 1835, the Graydon household was also the scene of the first advertised public anti-slavery meeting held in Harrisburg's white community. The supporters of colonization had already been holding public meetings, many of which were characterized informally as "anti-abolition" meetings. One such meeting was held at the Dauphin County Court House on the evening of 28 August. Attorney Charles C. Rawn recorded in his journal that he attended the meeting with "Hart and [Jacob B.] Weidman," and that he was asked to serve on a committee to draft an address containing the society's aims. This was the meeting later described in a pro-colonization petition to the United States Congress, a petition that was probably drafted largely by Rawn, as "a large and respectable meeting of the citizens of Dauphin County."

A few days later the colonizationists attempted to hold a second evening meeting at the courthouse, but County Commissioner Abraham Bombaugh barred the doors and the rowdy crowd could not get in. A wave of anger swept through the crowd and Charles Rawn wrote that the throng "showed signs of violence," but cooler heads prevailed and someone suggested that they could assemble in the large, open-air market sheds on the square.

The sweltering August heat had kept the proceedings of the previous evening's meeting quite subdued, but the heat wave had broken that morning and everyone was energized in the cool evening temperatures. This anti-abolition meeting was downright lively, with impassioned speeches delivered by J. J. Clendenin, publisher Henry K. Strong, and Rawn. In the spirit of the evening, attorney Rawn offered three resolutions, after which he moved that the meeting adjourn. The crowd would not allow any less than three or four cheers for the speakers. An article about the September first anti-abolition meeting appeared in the Pennsylvania Reporter, a strongly Democrat Harrisburg newspaper, mentioning the speeches made by the local men.57

Seeing the success of the anti-abolition rallies, Graydon and his supporters realized they had little time to waste in promulgating their opposing point of view, and they made plans for an anti-slavery event. A rally, such as the anti-abolitionist events that had attracted large crowds at the courthouse and a few days later in the market sheds, might be too ambitious, and it would no doubt attract troublemakers. Graydon perceived that a gathering in support of the anti-slavery movement in Harrisburg had to be persuasive in its nature, especially if it was directed at white residents, to whom it was the minority view.

Graydon hoped to sway many of those who held neutral viewpoints, and many of Harrisburg's citizens remained undecided between the true goals of the American Colonization Society versus the ultimate aims of the American Antislavery Society. He planned to appeal to the better nature of the town's citizens with a mixture of logic, pleadings for human rights, and perhaps even to play on the mistrust of the strong-arm tactics then being employed by Southern slave catchers. After all, the James Williams incident, in which an entire free African American family had been kidnapped near Middletown, was still very fresh in local people's memories. But who could make such a persuasive presentation?

"Free Discussion"

Alexander Graydon found his answer in the traveling speakers then being sponsored by the American Antislavery Society. Several months earlier, the society had begun sending speakers into eastern and south central Pennsylvania. The mission of these traveling speakers was "to arouse the public mind by addresses and lectures and to enlighten and convert individuals by private interviews -- especially to operate on ministers of the Gospel."

With the help of William Lloyd Garrison, the AAS was able to secure the oratorical talents of British anti-slavery lecturer George Thompson, the firebrand advocate of "immediateism," or immediate and complete abolition of all slaves. Thompson had two highly successful appearances in Philadelphia in March 1835, but did not venture further into the Pennsylvania heartland. In the spring of 1835, AAS agent James G. Birney spoke in Harrisburg, but his lecture apparently drew little controversy and even less interest, and no other anti-slavery speakers ventured into the region until the newly appointed agent Samuel L. Gould made his appearance in Gettysburg in early December of that year.

Gould followed in the examples set by earlier traveling lecturers, and debated a Gettysburg pro-colonization lawyer by the name of Cooper, who sought to stir up the emotionally charged issue of mixed race marriages by accusing the abolitionists of promoting "amalgamation," of the races. Such topics of debate typically drew large crowds. Gould's schedule included a stop in Harrisburg, so Alexander Graydon offered to host Gould's Harrisburg lecture in the parlor of his home, and proceeded to publicize the event, even extending an invitation to the newly elected Governor Joseph Ritner. The new Governor, who was rumored to have strong anti-slavery tendencies, remarked upon Graydon's invitation that he supposed it wouldn't hurt a man to listen to it, but he never did show up to hear Gould speak. He was not the only person to stay away. Hiram Rutherford, who was in the Graydon family parlor that day for the occasion, later recalled that "few were present."

It may not have been lack of interest that kept the audience small when Samuel Gould spoke to the town's white residents inside the abolitionist's house. Gould had earlier been delivering addresses to the African American residents of Harrisburg, speaking first to small groups, and then appearing before a large crowd in the Wesley Union Church on New Year's Day. When word of his speeches before the town's black residents reached the ears of local colonizationists, swift action was taken to censor him. Powerful local men approached the town's leaders and pressured them to prevent Gould from continuing. The Borough Council, feeling the heat from the opponents of abolition, met in special session on New Year's Day to draft and pass a resolution requesting that Gould "desist from his efforts in relation to the subject of slavery, which in this quarter can result in no benefit to the cause in which he is engaged, but may and most probably will produce consequences which he, in common with our citizens would have cause deeply to deplore."

Again, the foreboding language, with its lightly veiled threats, was used to try to stifle the anti-slavery voice in Harrisburg. To justify this resolution, the members of Council, "with deep concern," charged that Samuel Gould's addresses were "calculated to excite the colored population of this borough on the subject of slavery," and the resolution to stop him from speaking was a "mild" measure being taken against him "for the prevention of the mischiefs…which are so likely to ensue."58 Though harsher measures were not spelled out, they were implied, should he persist.

Gould fiercely defended his right to speak in town, replying to the Council that if he would heed their warning to keep quiet, he would "by that act become guilty of a base surrender of one of my dearest rights as a free man, and one of my most sacred privileges as an American citizen. . . the right of 'Free Discussion.'" So American Anti-Slavery Society agent Samuel Gould made his appearance in Alexander Graydon's house, speaking out against slavery in defiance of the Harrisburg Borough Council resolution. He also continued to exercise his right of free discussion, speaking with local African American citizens, which apparently was the greater sin, in the eyes of his opposition.

Although his oratory at these events was not as dramatic or as feisty as his sense of right, and his topics were somewhat mundane -- in remembering the event, Hiram Rutherford focused more on Gould's traditional Quaker dress than on his actual speech -- his appearance marked a watershed event for Harrisburg's white abolitionists. Samuel Gould was not the first outside abolitionist to speak in Harrisburg, but his appearances in town during the first few days of the New Year was as unnerving to the foes of abolition as it was fortifying to the few dedicated advocates for the "down trodden and oppressed" that gathered to hear him speak. Filled with resolve, they moved forward into the new year of 1836, determined to redouble their efforts and eager to work in concert with their African American brethren. Events began to move rather quickly after that.

The Harrisburg Anti-Slavery Society

Within days of Samuel Gould's speeches at Wesley Church and in Alexander Graydon's parlor, Harrisburg's white abolitionists moved to incorporate their sentiments into an organized body. About one hundred men and women met on 14 January in the Mulberry Street meetinghouse of Reverend Winebrenner's Church of God to organize the Harrisburg Anti-Slavery Society. In that meeting, it was decided that the Reverend Nathan Stem, the Rector of St. Stephen's Episcopal Church, would take the post of President, while Dr. William W. Rutherford and Mordecai McKinney would share the duties of the Vice-Presidency. Schoolteacher Samuel Cross was appointed to the post of Corresponding Secretary.59

Although the initial number of persons who met at the First Bethel to organize the society was surprisingly large for this period in Harrisburg's history, the actual number of dedicated anti-slavery activists involved was probably much smaller. Among the more active members of the new society were many of the same persons who had been working regularly with Alexander Graydon to distribute anti-slavery literature to local citizens and state lawmakers, including such activists as James W. Weir and hardware merchant William Root. It is significant that the newly formed society included women in its membership, recognizing the valuable service that many Harrisburg women were performing in the fight against slavery. It is equally significant, and ironic, that the new society included no African American members.

Even as Harrisburg residents were organizing a local chapter of the American Anti-Slavery Society, a strong push was underway to form a statewide organization to better orchestrate the efforts of numerous local societies. The national organization itself was only a few years old at this point, having been born out of the debates at the yearly national conventions of African Americans, which were organized in part by Junius Morel and held chiefly in Philadelphia.

Although those conventions, first held in 1830, focused initially on emigration and opposition to colonization, the 1831 convention saw the appearance of William Lloyd Garrison, who had published his first issue of the Liberator on 1 January of that year. Garrison's viewpoint, which was expressed strongly in the pages of his newspaper, was for immediate emancipation of slaves, as opposed to the gradual emancipation espoused by the long established Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Immediate emancipation appealed especially to Pennsylvania's African American citizens, many of whom had relatives still in bondage in the South, and it was in Pennsylvania that Garrison found valuable support, both for his newspaper, which even had a few paying subscribers in Harrisburg, and for his ideas, which were embraced by influential Pennsylvanians James Forten, who supplied both funds and the names of subscribers to the young publisher, and abolitionists James and Lucretia Mott.

Garrison's call for a national organization to embrace immediate emancipation met entrenched resistance from the PAS, whose members thought the national mood was too volatile and unstable for such a radical idea. He was able to marshal support from a variety of like-minded individuals, however, including Arthur and Lewis Tappan of New York and John Greenleaf Whittier of Massachusetts, and plans were laid for a convention, to be held in 1833, to form a national organization.60

The Philadelphia convention, at which the American Anti-Slavery Society was created, began on 4 December, and was held in the Adelphi Building on Fifth Street. Delegates entered the hall amid the jeers of passers-by, but experienced no significant interruptions during the course of the convention. Pennsylvania sent the largest delegation. Among its twenty-two delegates were African American representatives James McCrummel and Robert Purvis. The suburban counties were well represented by Dr. Bartholomew Fussell of Chester County, Thomas Whitson of Lancaster County, and James Miller McKim of Carlisle. Although women attended the convention, they were not given full delegate status.

By the end of the third day of the convention, a national anti-slavery society dedicated to the concept of immediate and uncompensated emancipation had been formed, a constitution had been written, and a declaration of sentiments had been drafted. The society office was shortly thereafter established in New York City.

Despite the interest of some Harrisburg citizens in these causes, the borough sent no delegates to the Philadelphia convention. Only James Miller McKim, of Carlisle, represented the greater Harrisburg area at the convention. Harrisburg's white abolitionists were not yet organized enough in 1833 to send a delegate. The same criticism cannot be leveled at Harrisburg's African American community. Although it did not send any delegates to the anti-slavery convention that year, it was active in the Philadelphia conventions of "colored people," having sent two delegates to that gathering the previous June, where they worked with the four delegates sent by Carlisle's African American community.61

Other communities in central Pennsylvania produced their own local Anti-Slavery Societies in quick succession, following Harrisburg's example. Gettysburg area abolitionists got together at McAllister's Mill, on Rock Creek, for a Fourth of July picnic in 1836, and after "competitive target shooting and patriotic toasts," the subject of slavery and free speech came up. Host James McAllister presided over the impromptu meeting, at which several formal resolutions were adopted, including protests against the squelching of "free discussion" by Congress.

"Free discussion" was a code phrase for the right to debate the legitimacy of slavery in the United States, and like other code phrases of this period, "the down trodden and oppressed" being one example already explored, this one also elicited strong emotions, depending upon the speaker's point of view.

A more formal meeting was held a few months later, in the hamlet of Two Taverns, to focus the aims of the Adams County anti-slavery men. At this meeting, a committee of correspondence was created, and the first steps toward the creation of a county auxiliary to the national Anti-Slavery Society were taken. Organizers planned to meet in the county courthouse, in Gettysburg, on 3 December 1836, and notices were placed in local newspapers advertising the gathering.

Unfortunately for the abolitionists of the county, the meeting also attracted large numbers of anti-abolitionists, who effectively hijacked the meeting and, with their vastly superior numbers, voted approval for pro-slavery platforms. Realizing that they had been politically ambushed, the anti-slavery men adjourned the meeting and made their way through the now unruly mob. They were pelted with rotten eggs and endured taunts and jeers. Fights broke out between the anti-slavery and anti-abolition men in the town square, until one of the organizers of the meeting, Michael Clarkson, led his embattled comrades to the nearby academy building at which he taught.

Another organizer, Professor William Reynolds, of Pennsylvania College, recorded the minutes of the first meeting of the Adams County Anti-Slavery Society on a school composition book found in the academy building. Thus forced from the courthouse by an angry mob, the Adams County men were finally able to form an anti-slavery society at Michael Clarkson's Academy. Founding members included James McAllister, Robert Middleton, Michael Clarkson, William Wright, Joel Wierman, and Professor William M. Reynolds.62

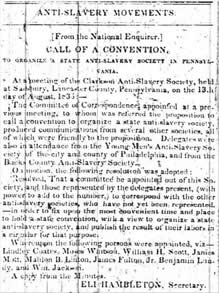

Members of the Clarkson Anti-Slavery Society call for a state convention. Summer 1836.

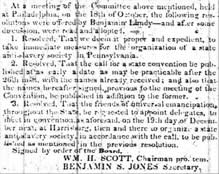

Members call for a state anti-slavery convention in Harrisburg, in December 1836. It would be held a few weeks later than planned.

Delegate John Greenleaf Whittier reported on the preceedings in Harrisburg for The Liberator.

The Harrisburg Anti-Slavery Convention

The need for a state organization to oversee all the local auxiliaries was apparent. Calls went out for a statewide convention to be held at the end of 1836, and Harrisburg was chosen as the location. The initial date set for the convention was 19 December 1836, but it was postponed until the following January. Delegates began arriving in town during the last week of January 1837, and the convention got underway on Monday, 31 January at Shakespeare Hall, on the northeast corner of Locust Street and Court Alley.

The Harrisburg Anti-Slavery Society appointed thirteen delegates to attend the convention in its hometown, while Junius Morel attended as the lone delegate of the Dauphin County Anti-Slavery Society, the town's African American organization. More than three hundred people from across the state, including about two hundred delegates and their servants, descended upon Harrisburg, filling most of the local hotel space.

Competition among local hoteliers for delegates was strong, and self-appointed convention correspondent John Greenleaf Whittier reported, in a published letter to William Lloyd Garrison, that great excitement was generated among the delegates by news that Garrison had arrived in town for the convention and had registered at Henry Buehler's Golden Eagle Tavern, on the square. Knowing that Garrison was not planning to attend, Whittier investigated, and sure enough, found Garrison's name on the hotel register. But upon further inquiry, he determined that "somebody connected with the establishment had placed [Garrison's] name on the arrival-book, in order to attract thither the delegates who were constantly arriving."

Even if Garrison was not in town, many other lights of the anti-slavery movement were. Whittier reported that Lancaster County Quaker Thomas Whitson, a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, "is now with us, firm as a rock, and true as steel." He also mentioned New Yorker Lewis Tappan, who was in town representing the national society, and Charles C. Burleigh, who he noted was "moving all before him wherever he goes." Present also was Dr. F. Julius LeMoyne, of Washington, Pennsylvania, an AAS agent and president of the Washington County Anti-Slavery Society, one of the first local societies to be formed in the state. LeMoyne had studied medicine at Jefferson Medical College, in Philadelphia, at about the same time as Harrisburg abolitionists William and Hiram Rutherford.

Dr. Bartholomew Fussell was again present, as was Lindley Coates, of Lancaster. Dr. LeMoyne was appointed President of the convention, while Dr. Fussell and Lindley Coates were appointed to two of the eight vice president posts. Reverend Nathan Stem, the president of the Harrisburg Anti-Slavery Society, also received an appointment as vice president. Whittier reported details of a petition by delegates for the use of the hall of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives for an anti-slavery lecture. Representatives George Ford of Lancaster County and William Morton of Beaver County supported the measure and presented resolutions giving use of the hall to the convention for the day and evening of 1 February, but the measure was not considered for debate. Representative Morton tried to get use of the hall for the evening only and succeeded in getting a debate on the question, but the state House still rejected any use of the hall by abolitionists. Delegates appeared to be unfazed by the rejection, which were probably proposed for the sake of publicity.

There were other attempts to take advantage of the proximity to state lawmakers. A resolution passed the first day cordially invited the governor, all state officials, and all state lawmakers to attend the convention. Apparently some did, as Whittier reported, "Many members of the senate and house of representatives were present," on the first day. He noted that many were not there as sympathizers, though, and that "the politicians of all parties who cluster around Harrisburg, are evidently alarmed at the signs of the times. They tremble to see the moral power of Pennsylvania about to be called into action."

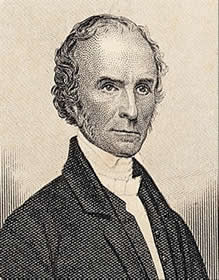

Delegate Benjamin Lundy helped organize the Harrisburg Anti-Slavery Convention.

One of the first serious petitions presented to the legislature was one proposed by Benjamin Lundy, who called for passage of a state law giving the right to a jury trial to accused fugitive slaves. Lundy was interested in keeping alive a bill that had been languishing in committee for several weeks. Lundy's petition was also presented by Representative Ford, and after considerable debate, it was moved along in the form of a resolution to the state Judiciary Committee to make further inquiries, but it would not make it much further. Most Pennsylvania legislators were satisfied with the current conditions of the state's Personal Liberty Laws, and did not want to cause additional irritation for their counterparts in Virginia and Maryland with stringent new standards.

If state representatives were not receptive to the requests of the abolitionists, Governor Joseph Ritner, "the sturdy farmer," was. Perhaps it helped that the governor's son, Henry A. Ritner, was attending the convention as a delegate from the Buffalo Anti-Slavery Society, of Washington County. The chief executive welcomed a delegation, which included John Greenleaf Whittier, to his Front Street home. Whittier wrote, "His Excellency met us at the door, shook us heartily by the hand, and ushered us into his plain parlor. He said he rejoiced that we had been able to hold our Convention in peace."

In fact the relatively uneventful four days of the convention, which was attended by nearly three hundred persons who "had the abolition doctrine so indelibly stamped upon their minds," and which was held in the midst of a notoriously anti-abolitionist town, was a novelty in itself. No violent incidents marred the proceedings during the entire run of the convention. If anything, Harrisburg's gentry enjoyed and were highly entertained by the extra hubbub created by the sudden influx of so many intent people. One attendee, in speaking with a local resident, was told, "Of all the incidents (which were many) calculated to attract the attention, none had the desired effect but the Circus and the Abolition Convention."63

Jonathan Blanchard in Harrisburg

Jonathan Blanchard addressed the Harrisburg convention several times. He spoke on the morning of the second day, chastising clergymen who identified slave holding as a sin, yet refused to take a stand for immediate emancipation of slaves. This speech was a not so subtle slap at Harrisburg's leading Presbyterian minister Reverend DeWitt, who tolerated the pro-Southern sympathies of many of his congregants while denouncing the concept of slavery in general. Blanchard charged that such men held "clouded moral perceptions," giving as an example some conversation he recently had with one such clergyman expressing these very views. He summed up his version of their argument with the following statement: "It is wrong, they say, for a Christian to hold slaves. Nevertheless, he is bound to hold them until he has perfectly satisfied himself that all the consequences of emancipation will be good." That reasoning, the New Englander explained, was blurring "the eternal distinction between right and wrong." In the style of a classic Great Awakening sermon, he thundered, "Theirs is the morality of the dark ages. It is like killing a miser for his money."

This was the style that must have endeared Jonathan Blanchard to his anti-slavery mentor Theodore Weld, leading Weld to recruit Blanchard for the cause. But Blanchard also had his sentimental side, and it came out a few days later in the convention. He spoke again in the late morning of the last day, calling for the recognition of the role of women in the anti-slavery cause. Blanchard recalled the work of British abolitionist Elizabeth Heyrick, whose 1824 pamphlet Immediate, not Gradual Abolition defined the aims of most of the women's anti-slavery societies in Great Britain, in contrast to the gradualist aims of the official, and male dominated, Anti-Slavery Society. Her name was already well known to many, if not most, of the delegates, as Heyrick's pioneering pamphlet had been republished in Philadelphia the previous year by the Philadelphia Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. Blanchard reserved high praise for her work, crediting her efforts for "the deliverance of 800,000 bondsmen of Great Britain."

Heyrick, a schoolteacher who was greatly influenced by the writings of Thomas Paine, had created a tight network in Great Britain of women's anti-slavery auxiliaries, all of which advocated immediate emancipation instead of gradual emancipation. In 1830, as treasurer of the largest female anti-slavery society in England, she played her trump card by threatening to withhold from the official male society all of the considerable funding supplied by these female-run auxiliary societies, unless the official organization reconsidered its views on immediate emancipation. As the female societies supplied over twenty percent of the general fund, the male-dominated official society had little choice but to acquiesce, and within months had adopted immediate emancipation as its goal. The ultimate triumph was achieved three years later, in 1833, when Great Britain abolished slavery throughout the empire.

Blanchard also cited female abolitionist Lydia Maria Child, who, like Heyrick, had also published in favor of immediate abolition, and more significantly, had begun the tradition of holding anti-slavery fairs as fundraisers. He also talked about Maria Weston Chapman, who, among her many other anti-slavery duties, took over management of the Boston Anti-Slavery Bazaar from Lydia Maria Child. Blanchard was followed by other speakers who praised the work of women in the movement, yet when the topic was finished, no resolutions were proposed or passed to give women more power in the organization. Just as at the 1833 Philadelphia convention, at which the AAS was created, women attending the Harrisburg convention were not permitted to hold delegate status.64

Jonathan Blanchard's appearance at the convention was fortunate, as the New England abolitionist spent only a year in Pennsylvania, from October 1836 to October 1837, as a traveling lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society. In that short time, though, the young, intense student of the ministry managed to inspire numerous influential people, and converted many to the abolitionist cause.

He was himself introduced to abolitionism at the age of twenty-one while serving as an instructor at Plattsburg Academy, in New York. The Vermont native, a graduate of Middlebury College, was teaching at Plattsburg in order to earn enough money to continue his studies for the ministry. He eventually enrolled in Andover Theological Seminary, taking with him the ideas that religious leaders ought to take a fierce moral stance against slavery, a concept that the seminary administration did not embrace. The young theologian became more and more dissatisfied with his situation, as he was unable to reconcile his strong anti-slavery beliefs with the practice being taught at his institution, so in the autumn of 1836 he left the seminary to work for the American Anti-Slavery Society as a traveling lecturer, or agent.

Theodore Weld and The Seventy

Prior to Blanchard's appointment, the anti-slavery agency system in Pennsylvania had been foundering outside of Philadelphia, with much of the work of spreading the word to the interior counties falling on the back of Samuel Gould, the agent who had been challenged in Harrisburg by the borough council, and who lectured in Alexander Graydon's parlor. In September 1836, the society added a number of new agents, including the conflicted seminarian Jonathan Blanchard, and another fiery young man, James Miller McKim of Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Although its work in Pennsylvania was lagging up to this point, the successes that traveling AAS agents had recently produced in Ohio, New York, and the New England states inspired society manager and former speaker Theodore Dwight Weld to rethink its methods, which had relied heavily on tracts and publications. Weld, who as a college student had been strongly influenced by evangelist Charles Grandison Finney and served as a member of his Holy Band, sought to heat up the agency system by melding the excitement and fervor of a camp meeting with the principles of "free discussion" and equality.

With the society's blessing, Weld began a search for a large number of passionate, intelligent, and charismatic men to spread the abolitionist message. He found many of them in his former alma mater, Oberlin College. Weld had been accepted by Oberlin after leaving Lane Theological Seminary along with a number of other students whose anti-slavery debates in 1834 were suppressed by the Lane administration because they were causing controversy. It was Weld who had initiated the debates by spreading the slave emancipation views he acquired from his work with Finney, and it was Weld who, as the spiritual leader of those suppressed, led the Lane Rebels in protest out of the seminary and on to Oberlin. Years later, in his search for talented evangelistically styled speakers, Weld turned to his contacts from Oberlin College.

He also scoured other venues, and found Blanchard mired in moral mediocrity at Andover Theological Seminary. Weld must have recognized a kindred soul in Blanchard, whose frustrations at not being able to convince his instructors that inaction in the face of moral injustice was not acceptable in the ministry. For his part, Blanchard's heart must have leapt to hear the older Weld express his Finneyesque conviction that "faith without works is dead." Weld recruited Blanchard for the job of traveling agent on the spot, adding him to his list of names.

Everyone recruited by Weld had to be highly dedicated to the cause. Almost all were talented, well-educated professional men capable of making a comfortable living in the world. As traveling agents for the American Anti-Slavery Society, however, they earned a grand total of eight dollars a week, plus expenses, "and brickbats in the bargain." Weld understood the sacrifice he was asking of his abolition proselytizers, and he undertook a novel team-building approach to induct them into their new roles.

All the new talent, including the young Jonathan Blanchard and James Miller McKim, were gathered together for an intensive training session at the society headquarters in New York in the late fall of 1836. There, under the tutelage of Weld, they were "drilled, disciplined and aroused" on the subject of slavery and the aims of the society. The sessions were described as being "for the purpose of kindling, warming, 'combustionizing' and in short getting the whole mass to a welding heat." Weld christened his army of fired-up agents "The Seventy," and turned them loose on the countryside, and in particular, he sent them down the turnpikes and back roads into the rural townships of Pennsylvania.65

Jonathan Blanchard had an opportunity to spend a month in the Harrisburg area before the "combustionizing" sessions in New York, and he spent the time busily preaching and lecturing to groups, families, and congregations. It was at this time, during the last week of October 1836, that he delivered his infamous sermon at Reverend DeWitt's Presbyterian Church, as described in Mary Ellen Graydon's account, which scandalized the "superlatively sensitive" congregants and mortified the church's pastor. During the next week, he lectured just north of the state capital, in the nearby towns of Dauphin, Halifax, and Millersburg, before returning to the borough.

The week after that he was in New York for Theodore Weld's training sessions, and by early December was back in Harrisburg, renewed and invigorated, and ready to take on the midstate's socially embedded colonizationists and politically entrenched pro-South sympathizers. He would need all of his energy and enthusiasm for the assignment. In the following weeks, twenty-five of his next thirty meetings were disrupted to some degree by the opposition, some to the extent of violent assault.

After each event, whether it went well or not, he would retreat to the welcoming Market Street parlor of the Graydon family, who played host to him during his months in Harrisburg, and recount the day's successes or failures. In each instance, he analyzed and dissected his performance, forever looking for new angles "to help the righteous cause." Finally, at the end of January, he could turn his attention to the convention, which was conveniently being held a few short blocks from where he was staying. Here, he would be preaching to the converted, but he did not pass up the opportunity to sit down and speak with anyone who could be an ally.66

Powerful Allies

One of those persons was the former state legislator from Gettysburg, Thaddeus Stevens, who, though currently in between terms, happened to be in Harrisburg during the abolitionist show at Shakespeare Hall. The Adams County legislator had been active in local colonization activities and anti-abolition rallies as late as 1835, but Stevens' anti-slavery sentiment had been strengthening and growing more radical during the previous year. Of particular importance to him was the concept of "free discussion," and he was repelled by the increasing tolerance for suppression of free discussion by the opponents of abolition. Only a month before the Harrisburg convention, Stevens' political mentor, Governor Ritner, had strongly attacked slavery in his annual address to the state legislature -- an address that many of Stevens' contemporaries thought bore his mark of collaboration:

These tenets then, viz: opposition to slavery at home, which, by the blessing of Providence, has been rendered effectual; opposition to the admission into the Union of new slaveholding States; and opposition to slavery in the District of Columbia, the very hearth and domestic abode of the national honor -- have ever been, and are the cherished doctrines of our State. Let us, Fellow Citizens, stand by and maintain them unshrinkingly and fearlessly.

Thaddeus Stevens treated Jonathan Blanchard to dinner just before the convention, and listened to his views on slavery and human rights. The crusty politician, who already bore the scars of nasty political battles, found in the young seminarian-turned-social-reformer a worthy and dedicated fellow warrior. He was anxious to bring Blanchard to Gettysburg, and to allow the fearless agent to pit his debating skills against the local anti-abolition men who that December had turned the anti-slavery meeting of William Reynolds, Michael Clarkson, and James McAllister into a melee. Stevens backed his commitment to Blanchard and the cause with a substantial donation, and the newly appointed AAS agent agreed to speak in Gettysburg after the convention.

Blanchard fulfilled that promise in March, appearing at numerous venues in that Adams County town, generally in front of crowds that included large numbers of rowdies, although members of the local anti-slavery society were also in attendance as moral support. The AAS agent appeared in a series of debates and spoke in defense of abolitionism, while local men Cooper and Smyser spoke against it, frequently offering resolutions denouncing the aims of the society.

Although most of the public debates at the courthouse were orderly, Blanchard was regularly jeered and occasionally pelted with objects, and sometimes had to dodge bricks, but with the help of Stevens, who appealed to the crowd to respect Blanchard's right to speak, he not only survived, but occasionally prevailed in these events.67 Blanchard and Stevens became good friends, and if the young AAS agent did not significantly enhance Stevens' anti-slavery beliefs, then at the least, in the words of one Stevens' biographer, "Blanchard's arguments buttressed Stevens' belief in antislavery."68

The arguments of Jonathan Blanchard seem to have significantly influenced the views of another important person in Harrisburg during his assignment here. Harrisburg attorney Charles Coatesworth Rawn spent a rainy November afternoon listening to the Reverend Blanchard speak on the topic of anti-slavery at the Harrisburg Masonic Hall, on Walnut Street. Rawn, as noted earlier, was a supporter of the local colonization society, and had even made a notable public speech a year earlier at the large anti-abolitionist meeting held in the borough's market sheds on the square.

C. C. Rawn was also one of the main composers of the petition presented to the U.S. Senate by Pennsylvania Senator James Buchanan, "praying that Congress would make appropriations to transport to Africa the free people of color; and that the constitution might be submitted for amendment on that point, if it does not now give the power." Although Rawn's name was originally associated with the petition, and was published by the local Jacksonian Democratic newspaper the Keystone in an article that ran alongside the petition when it reprinted it in January 1837 under the title "Memorial to Congress on the Subject of Colonization," there is evidence that he was already seriously rethinking his stance on colonization during this time. His willingness to attend a lecture on an opposing point of view the previous fall is one indication.

Jonathan Blanchard's 11 November 1836 speech at the Masonic Hall, a location that was frequently used as a public venue for such events, would have attracted an audience that included people on both sides of the issue. Crowds would gather to hear a discourse on any current topic if the speaker was skillful and engaging enough. If he was then challenged by someone in his audience on the points of his presentation and a vigorous debate ensued, so much the better.

Rawn does not appear to have gone to the lecture to challenge Blanchard on abolition, and he seems to have attended alone. Although his motives for going, and his impressions of the speaker and his topic are not noted in his journal entry that day, his later actions indicate that he was favorably impressed with what he saw and heard. Jonathan Blanchard left Harrisburg a few days after his speech at the Masonic Hall, to attend Theodore Weld's training in New York. Upon his return to Harrisburg, in early December, Charles C. Rawn again went to hear him speak.

It was on Sunday, 11 December, a day that Rawn described as being clear and beautiful. The devout attorney spent the morning in church with his wife and mother-in-law, and listened to the Reverend DeWitt conduct services in the Presbyterian Church, which was then located on Second Street, between Chestnut and Mulberry streets. That evening, Rawn again attended services in the Presbyterian Church, but the preacher for the evening services was the Reverend Blanchard. Rawn's journal entry for the day includes no comment on the younger preacher's performance, or reaction to his sermon.

Two days later, on 13 December, Rawn concluded a busy workday by entertaining visitors in his home. He welcomed the Reverend DeWitt again, at seven-thirty, and they talked about slavery. Rawn shared his opinion that slavery should be abolished in the nation's capital, an idea long advocated by Northern abolitionists and strongly resisted by Southern sympathizers. DeWitt, he recorded, seemed pleased to hear him say that. Rawn then recorded another opinion, which was much stronger. He wrote that he was "decidedly in favor" of opening up the topic of the abolition of slavery to public discussion.69 His endorsement of the concept of free discussion is another big step toward the views of the abolitionists, and away from the views of the colonizationists.

A State Society is Born in Harrisburg

Jonathan Blanchard and all the other two hundred delegates to the Harrisburg Anti-Slavery Convention had one overriding goal, in addition to spreading the gospel of abolitionism, which they hoped to accomplish during their four days in town. That was the creation of a state anti-slavery society to oversee and manage the activities and courses of the many local societies. A resolution was passed early on the first day of the convention, affirming that goal, stating, "This convention will now proceed to form a State Anti-Slavery Society." Committees were announced, and many of the Harrisburg delegates found jobs with one of the various committees formed to carry out the groundwork to accomplish the goal.

Alexander Graydon and Samuel Cross were appointed to the Committee to Draft a Report on Slavery in the District of Columbia. William W. Rutherford served on the Committee that reported on the slave trade being carried on between the states. Mordecai McKinney set about revising resolutions so that the business of the convention could be accomplished more effectively. One of his resolves was concerned with how the convention could make an appropriate response to the laws of Pennsylvania as they pertained to the recovery of fugitive slaves. As might be expected, this resolution triggered considerable debate, as every delegate had strong views on this subject. The convention president found it expedient to set up a separate committee just to handle this subject, and he appointed McKinney to lead it.

In addition, it was found necessary to add another resolution limiting each speaker to no more than two addresses not exceeding fifteen minutes each on any one subject. Verbose speakers were not the only problem that the convention officers dealt with on the first day. A brief resolution dispensing with "all professional titles" helped move things along, among the various doctors, attorneys, judges, and ministers of the gospel in attendance. With regard to religion, the Committee on Business quickly found that it needed to propose a rather unique resolution to limit religious expression during work sessions, if anything was to be accomplished. The members of the committee prefaced their resolution with a bit of explanatory text, perhaps to smooth over any ruffled feathers: "Inasmuch as this body is composed of persons conscientiously differing from each other in their modes of divine worship, but all acknowledging their dependence on Almighty God for guidance and instruction. Therefore, Resolved, That no outward form of religious devotion shall be observed by this Convention." The resolution passed unanimously. With such obstacles as speakers prone to prolixity, inflated egos, and conflicting religious views thus banished from the convention floor, the officers brought the first day to a close and adjourned the convention until nine o'clock the next morning.

The second day brought the creation of more committees and the reading of more congratulatory letters from the managers of local anti-slavery organizations. The resolutions offered ceased being solely functional and practical, as on the first day, and began to reflect the dogma of the Garrisonian abolitionists. One resolution, however, had a much more personal use, which was to mourn the recent loss of longtime abolitionists Thomas Shipley and Edwin Atlee. Both men were members of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, and both, as proponents of immediate emancipation, had been instrumental in starting the American Anti-Slavery Society. Shipley and Atlee, however, represented more to the delegates than just the passing of a previous generation of abolitionists. They were exemplars of the fully committed anti-slavery activist. Both men had lived their lives in devotion to their belief in racial equality and social justice, and had proved that devotion by repeatedly putting their fortunes, social standing, and even their lives in jeopardy on behalf of the African American residents of Philadelphia.

Shipley had personally protected fugitive slaves, had provided legal counsel to African Americans in need, and had shielded African Americans from harm during race riots in Philadelphia in the year prior to his death. Atlee had been similarly active on behalf of Pennsylvania's African American residents, and as a result, both men were held in high esteem by the Philadelphia African American community. Robert Purvis eulogized Shipley shortly after his death in a sermon at St. Thomas African Episcopal Church, in Philadelphia. At the convention, Harrisburg delegate Reverend Nathan Stem was appointed to the Committee to convey the condolences of the convention delegates to the bereaved families.70

On the final day of the convention, the preamble and constitution for the new state association were submitted and unanimously adopted, and officers were elected. F. Julius LeMoyne was elected to serve as the first President of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Harrisburg minister Nathan Stem was elected one of six Vice-Presidents. Alexander Graydon was appointed a manager of the society, as was William M. Reynolds, of Adams County.

It was at this point that the role of women in the struggle against slavery was recognized by a resolution, and discussed at length. Jonathan Blanchard, who seconded the resolution, recalled the deeds of Elizabeth Heyrick and mentioned southern activist Angelina E. Grimké, whose published works had been publicly burned in South Carolina, and Elizabeth Margaret Chandler, the young poet whose abolition-themed body of work regularly enriched Benjamin Lundy's Genius of Universal Emancipation, and whose collected poems were sold to fund anti-slavery causes long after her untimely death at age twenty-six.

It is intriguing that Blanchard stopped short of praising any Pennsylvania women then involved in the cause, citing "delicacy" as a forbidding reason. Apparently, he saw a danger in naming active Pennsylvania women. His references to Grimké and Chandler hint at the social forces that were often brought to bear against women who broke out of their traditional roles to embrace political or social causes. Charles C. Burleigh added his thoughts, remarking on the steadfast courage of some anti-slavery women he had witnessed, when assailed by a hostile mob: "We want that courage which can calmly meet shame, reproach, and insult, in the path of duty, offering no violence itself, and unawed by the violence of others."

Burleigh also cited the work of an African American woman, a former slave, then in New York, who stole her freedom, then rescued eleven other slaves "and is still devoting her time, her efforts, and the money her honest and persevering industry has acquired, to this work of humanity." Unfortunately, Burleigh did not name the woman who had brought eleven of her brethren out of slavery, but the speaker who followed him, Lewis Tappan, did. Tappan identified this woman as Hester Laing. At the mention of her name, fellow New Yorker Amos A. Phelps added that Laing had recently brought to the AAS office in New York a petition calling for the abolition of slavery in the nation's capital, with six hundred names, all collected personally by her.

A series of additional resolutions followed these outstanding examples of female activism in the cause, yet not one of the resolutions mentioned women, or attempted to give an increased management or governing role to women in the new state society. Women were in attendance at Harrisburg in admirable numbers, yet their work, which was every bit as important and vital to the success of the cause as that of the men, was relegated to one short resolution on the final day, which stated "we hail with great encouragement" their efforts and influence.71

The only true disagreement at the convention came with the introduction of a resolution calling on all abolitionists to make "the principles of universal freedom and of political equality" a test for all political candidates, and that they not vote for candidates who did not embrace those principles. The idea of forming an "Abolition Party," as some of the delegates believed was the underlying purpose of this resolution, was not palatable to many, and opposition to the resolution was voiced. Even if it was not for the purpose of establishing a distinct party, delegate Eli Dillin complained, "The resolution might be misunderstood." Dillin was backed up by James Loughhead, of Pittsburgh, who described the cause as "moral warfare. Its unpopularity had thus far kept our ranks pure. He dreaded to see the day, when from motives self-aggrandizement, unprincipled politicians should profess an attachment to our cause."

Poet John Greenleaf Whittier took issue with such ideas, noting that the national society had just spent considerable effort in gathering petitions across the country in support of the society platform against slavery in the District of Columbia, and against the admission of Texas to the union as a slave state. He asked "Why then give our votes one day for a member of Congress, who we know will throw our petitions unread, upon the table, and the next day send him these petitions, and wonder that he does not make an abolition speech upon them?...So long as we gave our votes in favour of such men,…we had no right to complain." Benjamin Lundy agreed, stating that he "could not, for one, forget his duty to the slave, even at the ballot box." In the face of such a disparity of opinion, the resolution was hastily withdrawn.

Once

that scrape was behind them, the officers moved to finish the

remaining agenda items, as the Harrisburg convention was

entering its final hours. One of the final pieces of business

involved setting a meeting location for the first annual meeting

of the newly established Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, and

Harrisburg was again chosen as "the most eligible place," after

which, the convention adjourned.72

Notes

50. Sharpe, Family Retrospect, 55-56.

51. "Resolution of the Legislature of Pennsylvania, December 24, 1829, Read and laid upon the table, Colonization Society," Serial Set vol. no. 199, Session vol. no. 1, 21st Congress, 1st Session, House Report 24.

52. "A Voice from Harrisburg," Liberator, 8 October 1831.

53. "Obituary, Dr. Hiram Rutherford," in Egle, Notes and Queries, Annual Volume 1900, 15:78-79; H.R. (Hiram Rutherford), "Pastors and Elders," in Egle, Notes and Queries, 4th ser., vol. 1, 100:323-324.

54.

Sharpe, Family Retrospect, 53-54.

Hiram Rutherford was harshly critical of Reverend DeWitt's

refusal to take a stand against slaveholding, later accusing the

beloved and long serving minister of lacking the courage to do

so. In published correspondence to columnist William Henry Egle,

in the last decade of the nineteenth century, Rutherford wrote

of DeWitt, "He was not a leader of men. Never was and never

tried to be. The servant, the slave of his congregation—what it

was, he was. Had it have been anti-slavery, he'd have been so,

too. As it was, he wasn't. By no chance did he ever make a new

departure. True as the north star, in his Zionward march, he

never failed to keep the middle of the road—the road of his

congregation." (4th ser., vol. 1, 100:324.) Rutherford's

charges, though, do not reflect DeWitt's personal struggle to

come to terms with this moral division that so sharply divided

his congregation. Through the 1850s, the pro-Southern, pro-

slavery stance became less popular in Harrisburg, and more of

DeWitt's flock reexamined their views in light of the perceived

abuses caused by the Fugitive Slave Law. On a personal level,

Reverend DeWitt occasionally met with one of his most trusted

congregants, Charles C. Rawn, to discuss slavery and related

issues. It appears that, over time, DeWitt came to accept or at

least tolerate the anti-slavery philosophy of the New School

theology, as he stayed with the New School congregation when the

Old School members of the congregation left in 1858 to form the

Pine Street Presbyterian Church. Rawn, incidentally, stayed with

the Old School Assembly, despite the views of the assembly that

slavery could be tolerated by the church in the South as a

necessary concession to preserve the Union. Ken Frew, Building

Harrisburg: The Architects and Builders 1719-1941

(Harrisburg: Historical Society of Dauphin County / Historic

Harrisburg Association, 2009), 52-53.

55.

Sharpe, Family Retrospect, 49-50.

Historian J. Howard Wert, a contemporary of Hiram Rutherford,

was similarly critical of Reverend DeWitt's treatment of

anti-slavery proponents in Harrisburg. Writing about the

activities of Harrisburg physician William Wilson Rutherford,

Wert says, "So pronounced were Doctor Rutherford's sentiments in

opposition to slavery that he was subjected to much persecution

in consequence. A prominent clergyman of the city made a canvass

of influential families, soliciting them not to employ Doctor

Rutherford as their family physician." Although Wert did not

identify the prominent clergyman by name, DeWitt was the only

borough minister holding enough social sway to attempt such a

maneuver. G. Craig Caba, Episodes of Gettysburg and the

Underground Railroad (Gettysburg: G. Craig Caba Antiques,

1998), 83-84.

56.

Sharpe, Family Retrospect, 55. A copy of Alexander

Graydon's advertisement for anti-slavery publications can be

found in the Pennsylvania Telegraph, 27 July 1837. A

transcript of the advertisement, including a list of all

twenty-nine titles he offered for sale, is at the Afrolumens

Project, at http://www.afrolumens.org/ugrr/dgraydon.htm.

One of the books distributed by Alexander Graydon to

Pennsylvania state lawmakers, and one available in his store,

was New York jurist William Jay's 1835 book An Inquiry into

the Character and Tendency of the American Colonization, and

American Anti-Slavery Societies. Harrisburg area

historian G. Craig Caba owns the copy of that book that was left

on the State Senate Chamber desk of Dr. George Smith, who served

in the State Senate from 1832 to 1836. An inscription inside of

the front cover reads, "Geo. Smith Esqr. Will please accept the

following pages written by the Hon. Wm. Jay of New York whose

reputation is no doubt well known to you. A copy is placed on

the desk of each member." The inscription was signed by M.

McKinney, Jno. M. Eberman, A. Graydon, Jas. W. Weir, Saml. Cross

"& other citizens of Harrisburg." The inscription in Caba's

book not only verifies the stories in Mary Ellen Graydon's

memoir, it also lists the names of Harrisburg's most involved

white anti-slavery activists in this early period.

57. Entries 28 August 1835 and 1 September 1835, "The Rawn Journals" (accessed 17 February 2009).

58. John L. Myers, "The Early Antislavery Agency System in Pennsylvania, 1833-1837," in Pennsylvania History 31, no. 1 (January 1964): 67-71; Egle, Notes and Queries, 4th ser., vol. 1, 100:324; Liberator, 13 February 1836.

59. George Ross, Biography Of Elder John Winebrenner--Semi-Centennial Sketch (Harrisburg: Dr. George Ross, 1880), 20; Barton, Illustrated History, 42.

60. Ira V. Brown, "Pennsylvania, 'Immediate Emancipation,' and the Birth of the American Anti-Slavery Society," Pennsylvania History 54, no. 3 (July 1987): 165-166.

61. Brown, "Immediate Emancipation," 166-169; Liberator, 15 June 1833.

62. G. Craig Caba, Gettysburg: 1836 Battle Over Slavery (Gettysburg: G. Craig Caba, 2004), n.pag. (5-8).

63. Liberator, 10 December 1836, 11, 18 February 1837.

64. Liberator, 18 February 1837; Elizabeth Heyrick, Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition, Or, An Inquest Into the Shortest, Safest, and Most Effectual Means of Getting Rid of West Indian Slavery (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society / Merrihew and Gunn, 1836).

65. Myers, "Early Antislavery Agency System," 68-77.

66.

Myers, "Early Antislavery Agency System," 78-79; Sharpe, Family

Retrospect, 52-53.

A report in the Liberator cited the Philadelphia National

Enquirer, just before the Pennsylvania Convention, to

report, "A mob was got up to assault Mr. J. Blanchard, during

one of his Lectures." This was during his work in Cumberland and

Adams Counties. "Recent Mobbing," Liberator, 28

January 1837.

67. Liberator, 17 December 1836; "Abolition Discussion," Gettysburg Star and Republican Banner, 20 March 1837. Thaddeus Stevens biographer Hans L. Trefousse, on the subject of Thaddeus Stevens helping to write Joseph Ritner's December 1837 Address to the Pennsylvania Legislature, simply notes, "It was said that he was instrumental in drafting the governor's message." Hans L. Trefousse, Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth Century Egalitarian (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001), 49-50.

68. Trefousse, Thaddeus Stevens, 50.

69. Entries 11 November 1836, 11 December 1836 and 13 December 1836, "The Rawn Journals" (accessed 17 February 2009).

70. Proceedings of the Pennsylvania Convention Assembled to Organize a State Anti-Slavery Society, at Harrisburg on the 31st of January and 1st, 2d and 3d of February 1837 (Philadelphia: Merrihew and Gunn, 1837), 1-36.

71. Ibid., 36-76.

72. Ibid., 76-78.

Caution: Copyrighted material. Published September 2010.

© 2010 George F. Nagle

This is the first in a series of books from the Afrolumens Project. Drawing on a large number of sources, and making good use of the treasure trove of information on the pages of the Afrolumens Project, this is the first truly comprehensive history of Harrisburg's African American community.