Harrisburg on the eve of Civil War

Study Areas

Kidnappings of Free Black Children in the 1820s

Philadelphia Becomes a Target

High demand for enslaved labor in the lower South meant that slaveholders in the upper South could get high prices for any enslaved persons they sold to local slave traders. This domestic slave trade increased tremendously after the importation of slaves was outlawed by Congress in 1808. Traders in the upper South scrambled to buy enough enslaved persons to transport south to the slave markets in Charleston and New Orleans. This potential for huge profits in human trafficking drew many into the morally repugnant but legal practice, setting up businesses in Maryland and Virginia. It also attracted criminals who understood that eager buyers often did not ask questions about the person or persons offered to them for sale.

Early Reports of Kidnappings

The kidnapping of free Blacks was not a new phenomenon when the Domestic Slave Trade blossomed after 1808. Philadelphia newspapers reprinted articles of such atrocities occurring in New York as early as the 1780s. The Freeman's Journal published "Extract of a letter from a gentleman in Charleston, to his friend in this city." in 1786. The correspondent in Charleston wrote:

"A negro man, a few days since, was offered by public sale to the highest bidder; . . . I enquired who he belonged to . . . he says his name was George Morris, that he was born free, and that he had left his certificate with James Shuter, clerk to William Backhouse, of New-York, and was shipped on board the sloop Maria, captain Tinker, by one Abrahams. He further says he came with one Griffith, a dancing master, to New-York, from Philadelphia.

The New York newspaper editor added the following observation and warning:

"I am full persuaded that many are kidnapped, brought from New-York and sold."Now riding in this harbour, the sloop Maria, capt. Tinker, and will probably sail for Charleston in a day or two. She has on board a considerable number of negroes; some of these distressed objects were soon ringing their hands, and praying to their relentless proprietors that they might be permitted to remain in New-York. . .It would be well for free negroes to be on their guard, lest they should meet with some kidnappers, and share the fate many have heretofore done. (The Freeman's Journal & North American Intelligencer (Philadelphia), 22 March 1786)

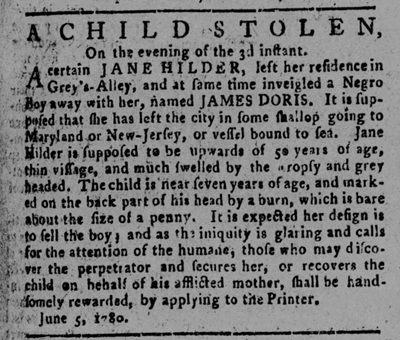

Kidnappings were already evident in Philadelphia at that time. A June 1780 report of a "stolen child" appeared in the Pennsylvania Packet, with an appeal for anyone with information to contact the editor:

A CHILD STOLEN,An incident in 1781, one year after Pennsylvania began the process of gradual abolition of slavery, illustrates how kidnappers did not always take victims from north to south. One man, identified as John Park, kidnapped a boy from a South Carolina slaveholder and in October 1781 attempted to sell him in Philadelphia:

On the evening of the 3d instant.

A certain JANE HILDER, left her residence in Grey's-Alley, and at same time inveigled a Negro boy away with her, named JAMES DORIS. It is supposed that she has left the city in some shallop going to Maryland or New-Jersey, or vessel bound to sea. Jane Hilder is supposed to be upwards of 50 years of age, thin vissage, and much swelled by the dropsy and grey headed. The child is near seven years of age, and marked on the back part of his head by a burn, which is bare about the size of a penny. It is expected her design is to sell the boy; and as this iniquity is glaring and calls for the attention of the humane, those who may discover the perpetrator and secures her, or recovers the child on behalf of his afflicted mother, shall be handsomely rewarded, by applying to the Printer.

June 5, 1780.

WAS LEFT at the subscriber's house, at the sign of the battle of Monmouth, in Market street, Philadelphia, on the 16th of October last, a MULATTO BOY, by a person who calls himself John Park. The said Park said the boy was his own property, and offered him for sale. He said he was obliged to go to the southward with some dispatches, and left the boy in my charge, and on his return he was taken up, and is now in Lancaster goal. As soon as the boy heard that Park was confined, he acknowledged that Park had taken him from Mr. Lyons, living on Pedee, in South Carolina, and says his name is John, but Park calls him Dick. Therefore his master is desired to come, prove his property, pay charges, and take him away.Summers continued publishing his appeal on behalf of John through December 11, 1782. During that time, in late October 1782, a five-year-old child named Sussex went missing. An alert and reward for information was immediately printed in a local newspaper:

Dec. 19, 1781. PETER SUMMERS. (The Freeman's Journal or The North American Intelligencer Philadelphia, 16 January 1782.)

Five Dollars Reward. LOST, in Second Street this afternoon, a NEGRO BOY, about five years old, had on a brown homespun jacket, a short red cloak, dark coloured trowsers, yarn stockings, and a small round hat. He answers to the name of SUSSEX. Whoever will bring him to the printer or inform where he may be found shall be intitled to the above reward. October 29, 1782. (The Freeman's Journal or The North American Intelligencer, 13 November 1782.)The published appeal and reward for information about Sussex ran for two weeks. A five-year-old child could hardly survive on his own in the city that long, making it probable that he came to a bad end, either killed or kidnapped.

As early as 1799, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen worked on a petition on behalf of the Black citizens of Philadelphia and environs praying for action by Congress. It was submitted to Congress on January 2, 1800, but no congressional action came from that appeal. Philadelphia experienced a rash of adult kidnappings in the early 1810s. In reporting on the abduction and subsequent sale in Georgia of a free Black woman from Delaware, the United States Gazette noted that the kidnapper in that case, William Nelson of Easton, Maryland, in 1817 appeared in the city accompanied by fellow Marylander Joseph Dawson, carrying documents to claim a married free woman and two sons in the Northern Liberties as slaves. They enlisted the enthusiastic help of lawman George F. Alberti, who himself would be at the center of many questionable "slave catching" activites in the coming decades. Last-minute efforts by friends of the family in the courts saved the woman and her two sons from being taken South, but not before Alberti savagely clubbed one of her sons as they were being captured. Within days of the release of the family, Nelson, Dawson and Alberti went after a free Black man on a nearby farm and forced him into a carriage. They were pursued and finally had to release the man.(United States Gazette, 4 July 1818)

Accounts of the kidnapping of free Black adults continued regularly into the 1820s, with free Black communities in Philadelphia, Wilmington, Baltimore and West Chester all experiencing abductions. In 1820 various Pennsylvania newspapers picked up an item from the Baltimore Gazette, reporting on the capture at Salisbury, Maryland of "noted Kidnapper, Dean Marvell, of Delaware, with an associate named Curtis Steene." Marvell, at least, apparently had been long involved in other abductions to be described as "noted Kidnapper." The pair was arrested for trying to sell a free Black man, whom they had beaten severely, named Peter Chance, of Wilmington. (Gettysburg Compiler, 28 June 1820)

Children Begin Disappearing

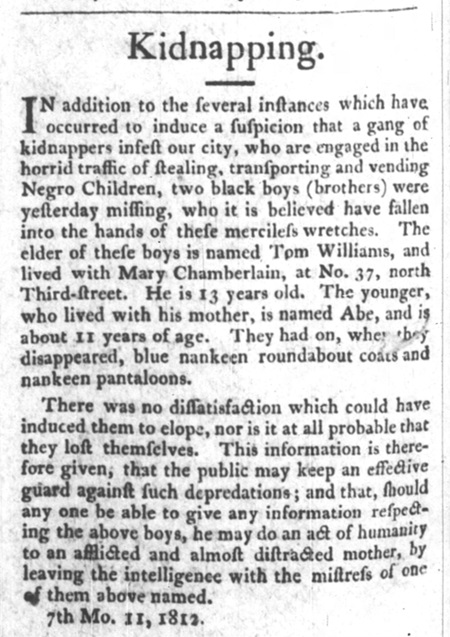

The nature of kidnappings took a particularly horrid turn as young children became targets. The Pennsylvania Gazette ran the following notice for several months in the summer, both to find information on the Williams brothers, but also to note that it was part of an alarming and ongoing series of incidents.

Kidnapping.

IN addition to the several instances which have occurred to induce a suspicion that a gang of kidnappers infest our city, who are engaged in the horrid traffic of stealing, transporting and vending Negro Children, two black boys (brothers) were yesterday missing, who it is believed have fallen into the hands of these merciless wretches. The elder of the boys is named Tom Williams, and lived with Mary Chamberlain, at No. 37, north Third-street. He is 13 years old. The younger, who lived with his mother, is named Abe, and is about 11 years of age. They had on, when they disappeared, blue nankeen roundabout coats and nankeen pantaloons.

There is no dissatisfaction which could have induced them to elope, nor is it at all probable that they lost themselves. This information is therefore given, that the public may keep an effective guard against such depredations; and that, should any one be able to give any information respecting the above boys, he may do an act of humanity to an afflicted and almost distracted mother, by leaving the intelligence with the mistress of one of them above named.

7th Mo. 11, 1812. (Pennsylvania Gazette, 19 August 1812)

The reach of the child kidnappers extended into the south central counties of Pennsylvania. The following brief article from the Baltimore papers was re-published verbatim in several papers in Philadelphia, Adams, and Lancaster counties:

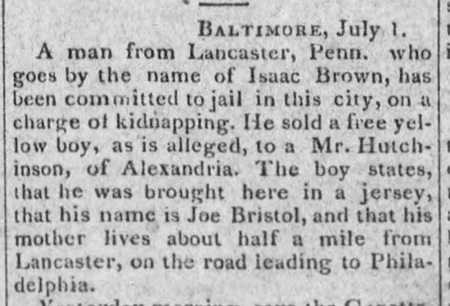

Baltimore, July 1.

A man from Lancaster, Penn. who goes by the name of Isaac Brown, has been committed to jail in this city on a charge of kidnapping. He sold a free yellow boy, as is alleged, to a Mr. Hutchinson, of Alexandria. The boy states, that he was brought here in a jersey, that his name is Joe Bristol, and that his mother lives about half a mile from Lancaster, on the road leading to Philadelphia. (National Gazette (Philadelphia), 2 July 1823)

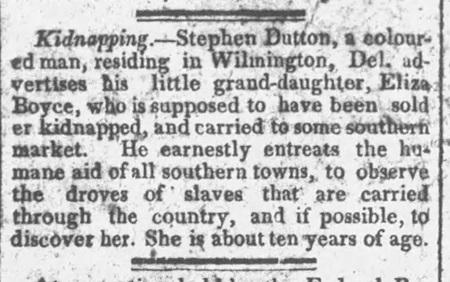

An 1824 appeal by Rev. Stephen Dutton of the Asbury African Methodist Church in Wilmington, and the grandfather of a missing ten-year-old girl, reveals the heartbreak and fear of Black parents in the greater Philadelphia area as the reports of missing children mounted.

Kidnapping. -- Stephen Dutton, a coloured man, residing in Wilmington, Del. advertises his little grand-daughter, Eliza Boyce, who is supposed to have been sold or kidnapped, and carried to some southern market. He earnestly entreats the humane aid of all southern towns, to observe the droves of slaves that are carried through the country, and if possible, to discover her. She is about ten years of age. (United States Gazette (Philadelphia), 3 September 1824)

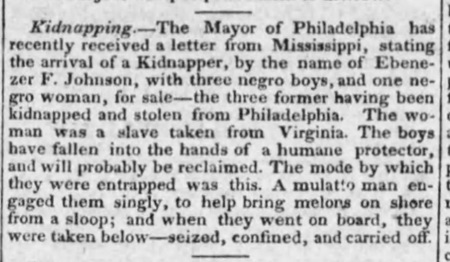

The kidnapping of Black children reached crisis stage in 1825. By the end of the summer of that year, more than twenty children were reported missing. City authorities and the local Black community felt helpless until, months later, a letter arrived in the office of Mayor Joseph Watson from a planter in Mississippi describing suspicious northerners who had suddenly arrived with groups of young boys for sale. Mayor Watson began an active investigation focusing upon the Deep South, sending High Constable Samuel P. Garrigues in pursuit of the missing children.

Kidnapping. -- The Mayor of Philadelphia has recently received a letter from Mississippi, stating the arrival of a Kidnapper, by the name of Ebenezer F. Johnson, with three negro boys, and on negro woman, for sale -- the three former having been kidnapped and stolen from Philadelphia. The woman was a slave taken from Virginia. The boys have fallen into the hands of a humane protector, and will probably be reclaimed. The mode by which they were entrapped was this. A mulatto man engaged tham singly, to help bring melons on shore from a sloop; and when they went on board, they were taken below -- seized, confined, and carried off. (The National Gazette, 17 February 1826)

Philadelphia Mayor Joseph Watson worked to obtain the necessary documentation to prove the free status of the children now held in protectivce custody in Mississippi. He dispatched High Constable Garrigues to the south, searching for additional clues. The exerpt below is from The Year of Jubilee, chapter six:

Following up on an active investigation, Philadelphia High Constable Samuel P. Garrigues spent three months searching for kidnapped city children in Louisiana and Mississippi. He found only two teenage boys, fifteen-year-old James Dailey and seventeen-year-old Ephraim Lawrence, and returned them to Philadelphia.

Ephraim Lawrence’s removal from the south was contingent upon the posting of a bond by Garrigues in a Mississippi courtroom guaranteeing the boy would be brought back at a set date to prove his free status. Fortunately the young man, as it was noted in the report, was “well known here by many white persons - and there will be no difficulty in producing evidence hereafter, as to his identity,” an obvious advantage in securing his freedom.

The younger boy, James Dailey, was not as lucky. He had spent four years in southern slavery, had suffered terrific beatings and abuse, and was in such a “miserable state of health” when he arrived back in the city, being unable even to walk, that his survival was in doubt. James Dailey had been born free in Philadelphia about 1813, but his family was afflicted with extreme poverty and he, like many children in similar circumstances, was placed in the city poor house. At age eleven, he and several other young boys were hired out by the overseers of that institution to a local man, Patrick Pickard, who claimed to be a tailor looking for apprentices. Instead, Pickard took young Dailey and several other boys to Louisiana where, posing as a Virginia slaveholder, he sold them all.

Pickard was not the only person in the area preying upon Philadelphia’s black children. Constable Garrigues then traveled north to Boston, where one of the kidnappers had been arrested for similar crimes in that city, to apprehend the man for trial in Philadelphia. After interrogating this kidnapper in relation to the Philadelphia kidnappings, the constable obtained information as to the possible whereabouts of some of the Pennsylvania children, and headed back south, altogether spending more than three months and traveling over two thousand miles in his search.

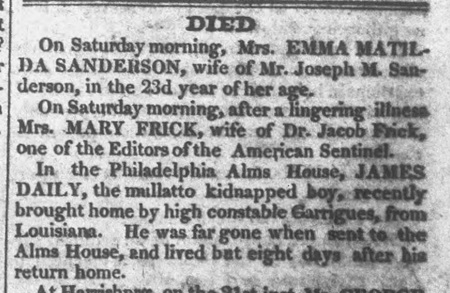

It was on this last excursion that Garrigues finally found Ephraim Lawrence in Mississippi, and then found James Dailey in Louisiana. Dailey was already in horrible health, and, upon explaining the deception to the young man’s owner, secured his immediate release. By the time they returned to Philadelphia, young Dailey could no longer walk, and was immediately admitted to the dispensary at the almshouse. He died eight days after his return. The certificate of death declared that the boy died of “debility, resulting from improper food, neglect during illness, and severe treatment. His person bore the scars of repeated whippings and blows and was emaciated.”

Although the case gained much publicity due to Dailey’s horrible death, the efforts of the local police paid off, as testimony from some additional recovered children helped convict some of the kidnappers. Such organized opposition to the gangs of “unprincipled men” was unique. No African American communities outside of Philadelphia had the resources or the political pull to offer resistance. To kidnappers, the field was wide open, and beginning in the 1830s, they took full advantage of almost every opportunity.

DIED

In the Philadelphia Alms House, JAMES DAILY, the mullatto kidnapped boy, recently brought home by high constable Garrigues, from Louisiana. He was far gone when sent to the Alms House, and lived but eight days after his return home. (United States Gazette, 29 January 1828)

Notes

Many of the kidnappings of children in the 1820s was the work of the notorious Patty Cannon gang. You can read more about Patty Cannon and her operations in Chapter Six of The Year of Jubilee.

Additional Sources

Smith, Eric Ledell, "Rescuing African American Kidnapping Victims in Philadelphia as Documented in the Joseph Watson Papers at The Historical Society of Pennsylvania," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 129, No. 3 (July 2005), pp 317-345.

The Year of Jubilee

Vol. 1: Men of God and Vol. 2: Men of Muscle

by George F. Nagle

Both volumes of the Afrolumens book are now available to read directly from this site.