Conductors, stationmasters, activists, politicians, slave hunters and others important to the history of the Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania.

Study Areas

Who's Who in Pennsylvania's Underground Railroad

George and Jane Chester

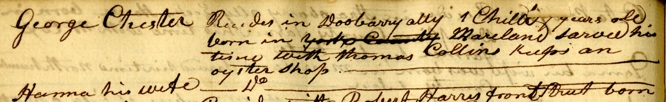

A prominent African American businessman who made his appearance in Harrisburg in the first two decades of the 19th century was George Chester. Chester is first found in the census of 1820, in which he appears as the head of an independent African American household of three people: one male and one female adult, and one male child. This small family unit matches the entry for the Chesters one year later, in the town’s registry of free African Americans. In that docket, George Chester, his wife Hanna, and seven-year-old child are all shown as residing in Dewberry Alley, in Harrisburg.

George told the record taker that he had been born in Maryland, and that he served his time with Thomas Collins in that state. Hanna Chester, his wife at the time, was also from Maryland. Chester would have been about thirty-seven years old by the time he registered his family with Chief Burgess Fahnestock. Significantly, Chester listed his occupation as the keeper of an “oyster shop.” George Chester’s oysters, and the restaurant in which he served these and other locally favored foods, would become quite popular and would soon play a prominent role in the development of abolitionist strategies by Harrisburg anti-slavery activists.

Something happened in the Chester household in the next few years, and Hannah, his wife, disappears from records. By 1825, George Chester was single and searching for another wife. In that year, the same year that several Maryland men hauled an accused fugitive slave before the county magistrate in the courthouse on Market Street, a block-and-a-half away from Chester's house, and caused the town's first documented anti-slavery riot, another Maryland refugee had entered Harrisburg and was attempting to mix in with the local free African American community. Her name was Jane Morris, and she was barely nineteen years old when she arrived, alone and probably frightened and intimidated, in town.

However, she did not lack courage and pluck, having run away from her Baltimore owner, a financier and land speculator named Dennis A. Smith, to whom she had been sold until she reached the age of thirty, by her previous owner, Judge George Gould Presbury, a noted jurist of Baltimore County. Faced with another eleven years of slavery, Jane headed north, following the turnpikes and waterways that had led so many freedom seekers along the same route to Harrisburg. Like these new arrivals, Jane sought the anonymity of a quiet position, and took work as a maid in the household of merchant Alexander Graydon.

Jane quickly endeared herself to Mr. Graydon and all the members of his family, including his sister Rachel, who at the time was still involved with the Sabbath School that she had helped organize in 1816. Rachel was recently married to Harrisburg lawyer Mordecai McKinney, and Jane went from working in the Graydon household to working in the new McKinney household, to help the couple manage their home. It was about this time that Jane, in her errands around town, met the oysterman George Chester. Chester was attracted to the young woman and a relationship developed.

In April 1826, they were married by the Rev. William R. DeWitt of the First Presbyterian Church in Harrisburg, and Jane moved into her own household with her new husband. At some point, the family built a house on the south side of Market Street, between Dewberry Alley and Fourth Street. At about the same time, George Chester established a firm address for his victual business, beginning a restaurant, or oyster cellar, on Market Street next to the courthouse, and his entire family took an active part in its operation and management. George and Jane Chester saw the commercial possibilities of positioning their restaurant in proximity to hungry barristers, bailiffs, and everyone who had business in the courthouse.

During the 1830s, African colonization presented a real and immediate threat to the future of Harrisburg's African American citizens. The push by whites to re-settle free Blacks in recently acquired colonies on the west coast of Africa was meant to drastically reduce the number of free Blacks in the states that were seeing growth in free Black communities.

Their response from Harrisburg's Black community was immediate and strong. In September 1831, they gathered in the only building that had always offered them a forum for their views, the humble log building at Third and Mulberry streets that was the African Wesleyan Methodist Church. There, the Reverent Jacob D. Richardson, who had just recently taken over from the founding minister, David Stevens, led the congregation in prayer and song, then convened a meeting of local citizens to formulate their response, as a united community, to the agitations of local colonization supporters.

Reverend Richardson, who was also the schoolmaster for the borough's African American children, was appointed chairman, and the well-respected Jacob G. Williams was appointed secretary. Richardson and Williams led the assembled citizens to hammer out a series of resolutions that were to be submitted to William Lloyd Garrison's newspaper, The Liberator, to express to the world the sentiments of Harrisburg's African American citizenry about African colonization. They called out the supporters of colonization on their "chimerical scheme for our transportation to the burning shores of Africa" by flatly rejecting their cultural connection to that colony as "land which we can no more lay claim to than our white brethren can to England or any other foreign country." The real objective, they stated, was grounded in a desire to preserve the status quo of slavery, "hence their object to drain the country of the most enlightened part of our colored brethren, so that they may be more able to hold their slaves in bondage and ignorance."

To further support the efforts of allies, the meeting added a resolution to "appoint Mr. George Chester, of Harrisburg, as agent for The Liberator, and will use our utmost endeavors to get subscribers for the same." This resolution recognized not only The Liberator and Benjamin Lundy's Genius of Universal Emancipation as valuable resources for the furtherance of their work, but it also formally recognized the work and restaurant of oysterman George Chester in organizing and providing a public place where those opposed to colonization could gather and discuss the latest developments.

The Chester family restaurant on Market Street remained an important gathering place, not only for those opposed to colonization, but for anti-slavery activists in general, since anti-colonization was, in its essence, anti-slavery. White and black activists gathered to discuss, plan and strategize, in a mixed-race effort to thwart enslavement in all of its forms. Although no evidence exists that the restaurant or even the Chester home itself ever gave direct aid to fugitive slaves, its importance to the anti-slavery movement and to the Underground Railroad is well established.

George Chester died in 1859. His family continued operating the restaurant, in different locations, for decades. Jane Chester became the premier caterer in Harrisburg during her long life. But most importatantly, the fight against slavery and the push for equal rights continued with their children, each of whom worked in their own way through Civil War, Reconstruction, and persistent institutionalized racism.

Notes

Population Schedules of the Fourth Census of the United States: 1820. Roll 102; Pennsylvania; Volume 7. Pennsylvania, Dauphin County. Microfilm in the Pennsylvania State Archives, Harrisburg, PA.

"Harrisburg Registry of Free African Americans, 1821."

One possibility regarding the place of origin for George Chester, based upon the location and approximate year of servitude to his former owner, is in Worcester County, Maryland, where Thomas Collins is listed in the county census as a slaveholder as late as 1810. If Chester was born in 1784 and manumitted at the traditional age of 28 or 30, he would have been free by 1812 or 1814, which allows for his appearance in Harrisburg between the 1810 and 1820 censuses with a wife and seven-year-old child.

Jane Chester's maiden and/or middle name is variously given, depending upon the source, as Jane Morris, Jane Marie, and Jane Mars. Morris seems to be the name most commonly accepted. The location of George Chester's residence on Market Street is given in the obituary of Jane Chester as "site of the present Hershey House." That location is 327 Market Street. In an advertisement placed by the Chester's for their restaurant in the 1856 Harrisburg city directory, it was identified as the Washington Restaurant, but it does not appear to have been commonly known by that name. Obituary of "Mrs. Jane Chester," Daily Telegraph, 19 March 1894, in Egle, Notes and Queries, 4th ser., vol. 2, 104:18; Theodore B. Klein, "Some Memories of East Market Street When I Was a Boy," in Egle, Notes and Queries, Annual Volume 1900, 4:21; Theodore B. Klein, "Old Time Reminiscences," in Egle, Notes and Queries, Annual Volume 1899, 37:184.

"A Voice from Harrisburg," The Liberator, 8 October 1831.

The 1889 obituary of David Chester, son of George and Jane, notes he was involved with "secret" organizations, without specifying the nature of those activities. Some have speculated that it refers to aiding fugitive slaves with his family. It is a widely held belief, from local lore, that the Chester home and restaurant was a station, but evidence remains elusive.

Afrolumens Project Home | Enslavement | Underground Railroad | 19th Century History | 20th Century History