Slavery

Slaveryto

freedom

Vibrant Black communities arise

from the ashes of slavery

Study Areas

York County, Pennsylvania

John Hall and Negro Elizabeth Take Defiant Stands

After 1780 and passage of the Gradual Abolition Act, Pennsylvania became an important destination for Blacks escaping bondage in nearby states. The southern border counties and Philadelphia in particular saw an influx of freedom seekers from Maryland and Virginia, prompting complaints from slaveholders in those states that Pennsylvanians were encouraging escapes by offering shelter and employment to escaped slaves.

The Constitution had a provision for the return of escaped slaves. The "fugitive slave clause" read

“No person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.”

The vague language relied on good faith cooperation between states to facilitate the capture and return of "fugitives from labor." That cooperation never happened and the anger of southern slaveholders with Pennsylvanians who accomodated freedom seekers was matched by the fear and indignation of Pennsylvanians who claimed southern slave catchers were rampaging through the countryside, bullying locals and terrorizing free Blacks. The animus reached a climax in a feud between Pennsylvania Governor Thomas MIfflin and Virginia Governor Beverly Randolph over a 1788 incident involving the removal to Virginia of a man named John who was set free by a provision of Pennsylvania's 1780 Gradual Abolition Act. The feud landed in the lap of President George Washington. The president saw that slavery, which had already been a sticking point between north and south in the production of the Constitution, had now become a prime source of friction along the border between slaveholding and free states, and the source of interstate crimes. Washington saw no way to separate the two issues. He asked Congress to resolve it permanently.

What resulted was the first Federal Fugitive Slave Act, which became law with Washington's signature in February 1793. It did not solve the problems.

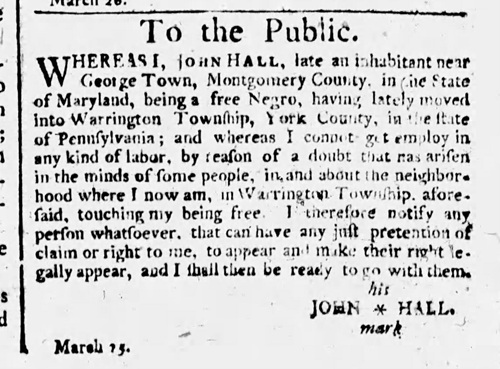

John Hall Notifies All Claimants to Come Forward

With its considerable concessions to southern slaveholders, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 made vulnerable not only freedom seekers hiding in Pennsylvania, but also free Blacks who had established their freedom through legal means, and even those who had been born in Pennsylvania. Slave owners, or persons working on their behalf, could now, without a warrant, immediately seize any Black person, take them before a local judge or magistrate, and with as little evidence as their oral testimony or a written deposition issued by a magistrate in their home state, remove that person out of Pennsylvania to enslavement in their home state, provided they proved their case to the local judge’s satisfaction.

It also placed in legal and financial jeopardy, with the imposition of a five hundred dollar fine and threat of possible civil action, any person that stood in their way. Citizens of border counties in Pennsylvania began to shy away from any contact with Black citizens that could be construed as “harboring” or providing protection.

Some free Blacks took extreme measures to establish their unencumbered status in the hopes of regaining a normal life. John Hall was a free Black man living in Montgomery County, Maryland, before the Fugitive Slave Law was passed. He moved to the free soil of Pennsylvania, settling in Warrington Township, York County, where he sought and found gainful employment.

With the passage of the new law, however, his fortunes changed. Local whites refused to hire him because they feared accusations of having provided shelter or comfort to someone who, as far as they knew, might be an escaped slave. Shortly after passage of the law, Hall found it necessary to prove his freedom by taking out an advertisement in the local newspaper that challenged anyone who could do so, to lay claim to him.

Hall complained that he could not “get employ in any kind of labor by reason of a doubt that has arisen in the minds of some people... touching my being free.” He therefore took the highly unusual and dangerous step of inviting anyone who would do so to call him a slave, stating, “I notify any person that can have claim to me" to come forward.

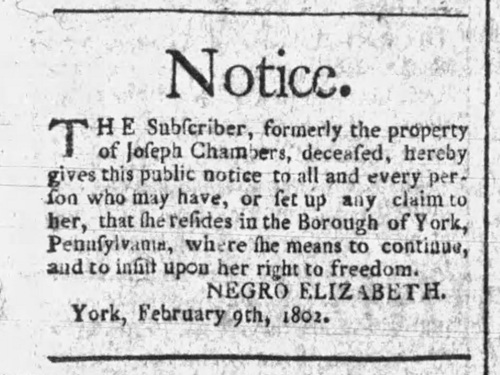

Elizabeth Means to Continue Living Free

Nine years after John Hall's challenge, another free person, Elizabeth, made an even more daring move. Elizabeth had been enslaved by York innkeeper Joseph Chambers. She obtained her freedom by some means after his death and established herself in the borough, living as a free woman. There may have been some question of her status, however, as she found it necessary, like John Hall before her, to publicly declare her freedom. While Hall's 1793 advertisement in a York newspaper acknowledged he would be "ready to go with" anyone who proved a claim of ownership against him, Elizabeth took a decidedly defiant stance, stating that she insisted upon "her right to freedom." Furthermore, she openly published her whereabouts to "all and every person who may have, or set up any claim to her." This "here I am, come and get me" approach was a bold attack on the presumption of bondage that burdoned Pennsylvania's free Blacks despite changes in the laws and slowly progressing moral attitudes of the society in which they lived.

Sources

- The Pennsylvania Herald and York General Advertiser, 27 March 1793

- The York Recorder, 24 February 1802<

- Paul Finkelman, Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson, 2nd ed. (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2001), 81-90

More Information

- For more on Joseph Chambers, see Slaves held by Joseph Chambers of York County, Pennsylvania.

- For a discussion of the writing of the 1793 Fugitive Slave Law, see The Year of Jubilee, chaper six, "No Haven on Free Soil."

- For an example of the dangers faced by free Blacks in Pennsylvania, see "Pass for Edward Butler, a Free Black Man, 1806."

- For a collection of articles on the dangers faced by free Blacks from kidnappings, see the Kidnapping section of The Violent Decade .