|

|

|

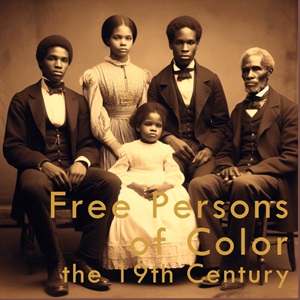

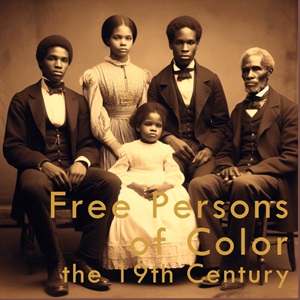

Study Areas Free Persons of Color |

Harrisburg CemeteryBlack History Perspectives Tour |

Tour stop 4: Charles Coatesworth Pinckney Rawn, "this Nation will yet weep"Charles C. Rawn (1802-1865)Harrisburg lawyer Charles C. Rawn was one of two lawyers hired by Blacks and sympathetic whites to defend those accused of being fugitive slaves during the days of the federal Fugitive Slave Act. Rawn and Mordecai McKinney frequently rushed to the defense of hapless men, women and children brought before the federal slave commissioner, Richard McAllister, whose office was in Harrisburg. All too often, though, their efforts were in vain, as the federal law stifled the rights of Blacks accused of being fugitives, and Commissioner McAllister, sympathetic to slaveholders, remanded most of the fugitives back to slavery. Born in 1802 in Washington D.C. to David Rawn and Elizabeth Cheyney, Charles' father died when he was seven years old, and his mother moved the family to Delaware County in Pennsylvania. Charles studied at West Chester Academy, then came to Harrisburg in 1826 to study law with his cousin, Francis Rawn Shunk. Shunk, a Democrat, was elected Governor of Pennsylvania in 1844 and served to 1848, resigning due to ill health. Charles was admitted to the Dauphin County bar in 1831. Like Mordecai McKinney, the Harrisburg judge and lawyer with whom he worked to defend fugitive slaves, Rawn opposed slavery as a Free-Soil Democrat, serving as a delegate from Dauphin County to the state convention in 1853. At about that time he was also heavily involved with representing Blacks who had been arrested in Harrisburg and accused of being fugitive slaves. The previous tour stop, Mordecai McKinney, discussed the 1850 Federal Fugitive Slave Act and the work of McKinney and Rawn in trying to defend those ensnared by that legislation. One case in particular, however, would propel Rawn deeper into the depths of slavery than he had ever before gone. A Harrisburg man, James Philips, was arrested by constable Henry Loyer in June 1852 as the escaped slave of Henry T. Fant of Fauquier County, Virginia. Philips was hauled into Commissioner McAllister's office for the hearing where he was represented by Rawn and McKinney. The witnesses for the claimant admitted that the escaped slave had been gone for fifteen or sixteen years, and that they were only eleven or twelve years old when he ran away. They claimed positive identification only because James Philips bore a supposed family resemblance to slaves still in bondage in Virginia. The Commissioner ruled against Philips and produced a writ already filled out to turn the man over to the Virginians. The following day the slave catchers took Philips to Richmond where they sold him to slave dealer William A. Branton for $505. The shock of seeing a longtime and well known resident of Harrisburg brutally hurled into slavery spurred several local men into raising money to buy James Philips' freedom. Philips, married with two young children, was employed by merchant John H. Brant, who gave $300 toward his redemption. Dr. William W. Rutherford and coal dealer Ely Blyers raised the rest of the $800 demanded by Branton for the release of Philips. Charles C. Rawn was the person chosen to travel to Richmond on a mission of mercy to free James Philips. He recorded his experiences in a personal journal, writing with shocked disbelief at what he witnessed each day. The daily entries, recorded without hyperbole, take an unflinchingly raw look at a working slave market and exist today as a testament to the horrors of the slave auctions. On July 10, 1852, having just arrived at a local slave market frequented by Branton, Rawn wrote: While looking round I witnessed the most horrible, and Heaven defying scenes of the inspection & sale of 5 or 6 females ranging from 17 to 26 or 30 years old, 3 of them with infant children...another stout strong looking man 40 to 44 yrs old all put up 'warranted sound' and title perfect...The man was taken behind a screen, his trowsers stripped down to his feet and his shirt pushed on to his waist as though his private parts, behind & spine and thighs and legs were the parts most desirable to be perfect...He was put on the "block" as they call it, being something like a large table or platform abt 6 ft by 4 mounted by 4 or 5 steps where the slave stands while the auctioneer sells him.On July 15, 1852, Rawn recorded: I saw one very fine tall & large looking yellow woman (about 25 or 30 years of age) long, straight black Indian looking hair & Indian face & soft & sorrowful expression. She looked permanently pensive & sad & when put on the "block" while the sale of her was going on, I saw the big tears slowly & as if imperceptibly to her trickling down her cheeks--she seemed instinctively modest & disdainful about free examinations usually made of their ancles [sic] and legs and when the black man whose business it was to show them off &c was on one and the only one raising her dress & clothing, she jerked them out of his hand with decided promptness.Rawn went on to describe Branton's "jail" where he saw Jim Philips, and wrote, prophetically: The more I see however the More I detest & abhor the accursed business. That it is accursed of Heaven I as firmly believe as that I believe in the Justice and goodness of God. And this Nation will yet weep over this National sin of slavery & a slave trade in sackcloth & ashes and the severer Judgment of a righteous God who will surely visit us as a Nation with our National sins.Rawn did redeem James Philips for the agreed-upon sum of $800, and the party returned to Harrisburg to resume their lives. Philips continued to work for John Brant as a teamster and Rawn continued to fight slavery in the courtroom and the hearing room until his death in 1865.  NextAndrew M. Bradley Black Statesman and Civic Leader

SourcesFor an older biography of Charles C. Rawn, Rawn's work for in defense of Blacks accused of being

fugitive slaves is well documented in Rawn's journal detailing his trip to the Richmond slave

markets is excerpted in Rawn's work with the Free-soil Democrats is from (Washington DC) The National Era, June 2, 1853. This newspaper is digitalized online at Accessible Archives. |

|

Afrolumens Project Home | Enslavement | Underground Railroad | 19th Century | 20th Century

Original material on this page copyright 2024 Afrolumens Project

The url of this page is https://www.afrolumens.com/rising_free/hbgcem05.html