Study Areas:

"Uncle

Tom's Cabin"

The Stage Play in Harrisburg

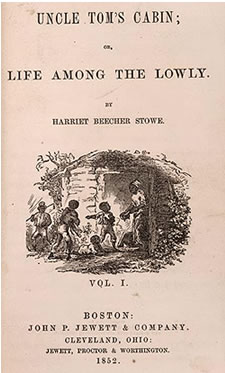

Despite central Pennsylvnia's distaste for abolitionist politics, Harriet Beecher Stowe's abolitionist novel Uncle Tom's Cabin was favorably received in the region, to the point that copies sold as fast as stores received shipments, and volumes sometimes became difficult to find during the first year of its release. In Lancaster, bookseller W. H. Spangler advertised through this early period that he had already sold one thousand copies of Stowe’s novel, and was prepared to “supply all demands for the book.”

Theater

troupes, always the first groups to incorporate popular

culture in their repertoires, quickly developed stage versions of the

widly popular book. In February and March of 1854, the traveling stage

production of “Uncle

Tom’s Cabin” played

in Harrisburg, and for a period of two weeks straight, the

theater was packed with local residents.

Though sales of the printed book remained steady through the coming years, Uncle

Tom, Little Eva, Topsy, Eliza, and George Harris did not return to

the stage in Harrisburg until the city was well in the grip of Civil

War.

Theater

troupes, always the first groups to incorporate popular

culture in their repertoires, quickly developed stage versions of the

widly popular book. In February and March of 1854, the traveling stage

production of “Uncle

Tom’s Cabin” played

in Harrisburg, and for a period of two weeks straight, the

theater was packed with local residents.

Though sales of the printed book remained steady through the coming years, Uncle

Tom, Little Eva, Topsy, Eliza, and George Harris did not return to

the stage in Harrisburg until the city was well in the grip of Civil

War.

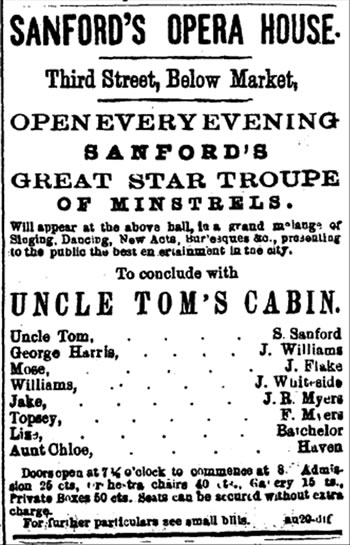

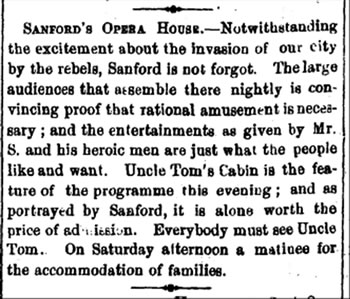

In June of 1863, thousands of Confederate soldiers were advancing steadily northward from the Potomac River into the Pennsylvania heartland, menacing not only the rich Cumberland Valley, but threatening to sweep aside local militia units, march right up to the Susquehanna River and cross the Camel Back Bridge into Harrisburg. Local newspapers were filled with dire headlines and grim invasion news. Editors found themselves torn between sensationalizing recent events, which sold newspapers, and a civic duty to urge citizens to remain calm. George Bergner, editor of the Daily Telegraph, managed to do both, simultaneously pumping up the war frenzy while urging calm. In an ad for a local theater, the paper reminded, “Notwithstanding the excitement about the invasion of our city by the rebels, Sanford is not forgot. The large audiences that assemble there nightly is convincing proof that rational amusement is necessary.”

The “rational

amusement,” on this occasion, was quite appropriate

to the emergency. Sanford’s Opera House was staging “Uncle

Tom’s Cabin.” This was not, however, the traveling stage

version based strongly on Harriett Beecher Stowe’s best selling

novel. Samuel S. Sanford’s adaptation, dubbed “Sanford’s

Southern Version,” or “Real Life in Old Kentuck,” purported

to tell the authentic story of slave life on the plantations. In popular

burlesque style, it lambasted abolitionism and featured the character

Aunt Chloe as an unhappy free resident of Cincinnati, singing a song

called “I’d radder be on de Old Plantation.” The character

Topsy accompanied herself on the banjo and sang “Dere’s No

Use Talking When a Nigger Wants to Go.”

The “rational

amusement,” on this occasion, was quite appropriate

to the emergency. Sanford’s Opera House was staging “Uncle

Tom’s Cabin.” This was not, however, the traveling stage

version based strongly on Harriett Beecher Stowe’s best selling

novel. Samuel S. Sanford’s adaptation, dubbed “Sanford’s

Southern Version,” or “Real Life in Old Kentuck,” purported

to tell the authentic story of slave life on the plantations. In popular

burlesque style, it lambasted abolitionism and featured the character

Aunt Chloe as an unhappy free resident of Cincinnati, singing a song

called “I’d radder be on de Old Plantation.” The character

Topsy accompanied herself on the banjo and sang “Dere’s No

Use Talking When a Nigger Wants to Go.”

In Sanford’s version, Eliza and George Harris stayed on the plantation to “jump de broom” in Uncle Tom’s cabin, to live a satisfyingly bucolic life in Kentucky. The final scene, dubbed “Such a Happy Time,” featured “congo dances, reels, camp meeting chants,” and a ‘corn shucking reel,” with the entire troupe singing

Oh! White folks, we’ll have you to know,

Dis am not de version of Mrs. Stowe;

In her de Darks am all unlucky,

But we am de boys of Ol Kentucky.Den hand de banjo down to play,

We’ll make it ring both night an day;

And we care not what de white folks say,

Dey can’t get us to run away.

Samuel S. Sanford, a veteran minstrel performer since 1840, wrote and first staged this version of Stowe’s serialized story in 1853 in a specially built Philadelphia minstrel hall, called Sanford’s Opera House, initially located on the corner of Twelfth and Chestnut streets. Following a disastrous fire, Sanford’s troupe of minstrel performers moved to a new home in 1855, opening in a hall at Eleventh Street with partner Freeman Dixey, where the Sanford Opera Troupe continued to perform until April 1862, when Sam Sanford split with Dixey, moved the troupe to Harrisburg and opened in a hall on the corner of Blackberry Alley and South Third Street.

Here,

Sanford’s troupe offered a varied bill of amusements

including burlesque, dancing, comedy, singing, and of course minstrel

shows. For the latter, the troupe performed in blackface, with Sam

Sanford as the star. In his version of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” which

by 1862 had become one of their signature pieces, Sanford played

the role of Uncle Tom.

Here,

Sanford’s troupe offered a varied bill of amusements

including burlesque, dancing, comedy, singing, and of course minstrel

shows. For the latter, the troupe performed in blackface, with Sam

Sanford as the star. In his version of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” which

by 1862 had become one of their signature pieces, Sanford played

the role of Uncle Tom.

This pro-Southern version played very well in Harrisburg—Bergner wrote that “the entertainments as given by Mr. S. and his heroic men are just what the people like and want”—attracting large audiences through its run. Sanford charged twenty-five cents for general admission, fifty cents for private box seats, and offered gallery seating for just fifteen cents. Traditionally, African American patrons were restricted to the galleries in Harrisburg theaters. Whether any chose to overlook the overtly racist and patronizing bill of fare in order to avail themselves of a little “rational amusement” from Sanford’s “Great Star Troupe of Minstrels” in this time of crisis is not known.

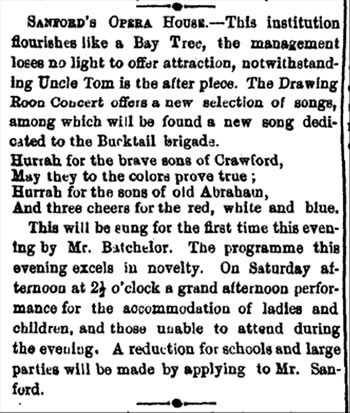

In

a small city such as Harrisburg, however, even the most popular plays

had limited appeal after a few nights. Fresh material was always needed

to keep the house full. Within a week, "Uncle Tom's Cabin" was

finishing its run and new material

was already on the playbill. In this instance, a "new song dedicated to

the Bucktail Brigade" drew the attention of the newspaper editor. With

the invasion emergency intensifying, more and more soldiers were pouring

into the city, along with many thousands of military non-combatants, reporters,

drovers, and refugees. The patriotic fare was surely meant to lure these

newcomers and visitors into the theater on South Third Street.

In

a small city such as Harrisburg, however, even the most popular plays

had limited appeal after a few nights. Fresh material was always needed

to keep the house full. Within a week, "Uncle Tom's Cabin" was

finishing its run and new material

was already on the playbill. In this instance, a "new song dedicated to

the Bucktail Brigade" drew the attention of the newspaper editor. With

the invasion emergency intensifying, more and more soldiers were pouring

into the city, along with many thousands of military non-combatants, reporters,

drovers, and refugees. The patriotic fare was surely meant to lure these

newcomers and visitors into the theater on South Third Street.

The Bucktails memorialized in the song sung by troupe member W. Batchelor were apparently the four companies of men from Meadville and Titusville, Crawford County, who came to Harrisburg at the end of the previous summer to be mustered into the 150th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, under the command of Colonel Langhorne Wister. Wister was the scion of a Philadelphia industrialist family, and at age eighteen he settled in Duncannon to clerk at his family's Duncannon Iron Works.

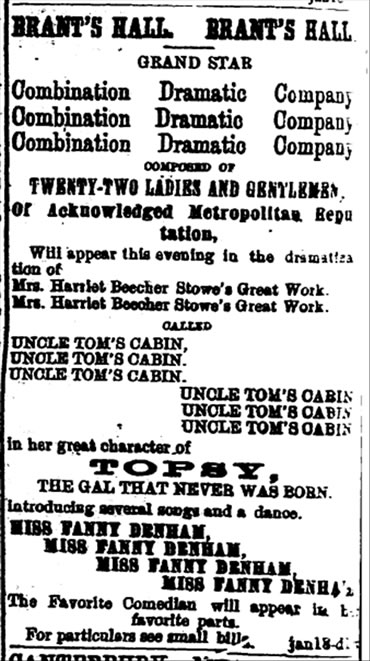

The

more traditional adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin came to Harrisburg

in January

1864, performed by the Grand Star Combination Dramatic

Company. This version differed substantially from what Harrisburg had

previously seen in Sanford's hall. For one thing, this was the "dramatization

of Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe's Great Work," as opposed to "Sanford's

Southern Version."

The

more traditional adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin came to Harrisburg

in January

1864, performed by the Grand Star Combination Dramatic

Company. This version differed substantially from what Harrisburg had

previously seen in Sanford's hall. For one thing, this was the "dramatization

of Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe's Great Work," as opposed to "Sanford's

Southern Version."

The cast was also significantly larger, being composed of "Twenty-Two Ladies and Gentlemen of Acknowledged Metropolitan Reputation." Sanford's version, in compariosn, was performed by eight minstrel players, some of whom were local amateurs.

The real difference, however, was in the nature of the dramatic troupe itself. The 1864 performance was being staged by a touring Combination Dramatic Company, as opposed to Sanford's reportory Minstrel company. Combination companies presented a brand new type of theatrical experience. Whereas a reportory company staged and performed a variety of shows, a combination company performed only a single show, taking it from town to town. This enabled it to use specialized scenery, elaborate cosutming, and to employ expensive but impressive special effects.

The star performer was Miss Fanny Denham in the role of Topsy, the eight-year-old slave girl who grew up on a large plantation with no knowledge of her mother or family. A 1910 Edison recording of a scene from this play (although not this dramatic troupe) gives a good idea of what it sounded like to Harrisburg audiences:

Edison Amberol cylinder "Entrance of Topsy" from "Uncle Tom's Cabin," 1910, performed by Len Spencer and Company. National Park Service collection. Public Domain.