Study Areas

Anti-Slavery

J. Miller McKim Visits a Slave Prison

3 March 1838

Letter of J. Miller McKim, published in

The Colored American, 3 March 1838.

LETTER

Washington, D.C. Feb. 6th, 1838.

MY DEAR BROTHER, -- At the Convention

held at Harrisburg, it was agreed upon by the delegates from the western

part of Penn. and myself, that I should proceed to that region as soon as my

engagements would permit, with the view of laboring there in the duties of

my agency. But being desirous to visit our national capitol, not only for my

own participation, but because I supposed in so doing I might subserve the

interests of our cause, I was induced to pursue a rather circuitous route to

the scene of my future labors, for the purpose of taking this city in my way.

An account of some of the incidents with which I have met, in the meantime,

I think will not be without interest to you and your readers.

I left Harrisburg last Tuesday morning, in

the stage for Baltimore. Nothing occurred to beguile away the tedium of

our journey, excepting a little disputing on the subject of abolition, until

we had crossed the Maryland line, some distance. There we stopped to take in

passengers. Among these was a young slaveholder, belonging to a very wealthy

family of that neighborhood. He was a fair specimen of southern 'bloods,' and

one of the proudest and most profane men I ever saw. When I first noticed him,

which was in the tavern before we got into the stage, he was amusing himself

with a well trained but very fierce bull-dog, which he would start with a hiss

after some of the men about the house, and stop him before he could bite them.

The people of the tavern endured his overbearing rudeness with a very ill grace,

but were unwilling as I supposed to lose his patronage, by crossing him. When

he got into the stage, he seemed disposed to give us a specimen of his spirit,

in the curses he heaped upon his unoffending slave, who brought his baggage

to be put into the boot. After we started and

had rode some distance, he espied a little colored boy on horseback, at some

distance from the road. He demanded of him, in a fierce and most profane manner,

what he was doing there. Of course, the reply of the little boy, at such a

distance, could not be heard for the noise of the coach. He called upon him

to come up to him -- the boy hesitated, as the stage was going very fast. He

then in a tone and manner which seemed to frighten the boy, ordered him immediately

to ride up along side of the stage. This he did, and rode along with the stage

until his master, so called, had catechized him sufficiently. He then gave

him some curses and dismissed him.

These things seemed to excite little sensation among the other passengers,

but to me it was exceedingly painful. It was painful to witness the horrid

effect of slavery upon the temper and morals of the master; it was touching

to see the poor boy's spirit broken by tyranny, and crouching with abject fear

before such a consummate young ruffian, and it was a matter of painful reflection

to think, that this fellow had absolute power over these and others of his

fellow-men, and to have proof furnished that he made abundant use of that power.

When he left the stage, which he soon did, one of the passengers observed,

that was Young Mr. J. P_____, a high fellow, but having

some fine traits of character -- he loses a good deal of money gambling, but

fortunately he is not intemperate -- adding that he was now on his way to Philadelphia

after a runaway slave.

We arrived in Baltimore that evening, and at 9 o'clock the next morning set

out for Washington. -- As the country through which we passed is very barren

and devoid of interest, I threw myself up to my own reflections. From these

I was not aroused until we reached a stopping place about 12 miles from this

city. Here as I was getting out of the car, a man opened the door of a baggage

car which was next before ours, and was urging in a colored lad -- "come

get in -- hurry away -- get in." Then another was brought and put in --

and another in the same way. Then came the mother with an infant on her bosom

-- the tears pouring over her cheeks, and sobbing as though her very heart

was broken. Last of all came the sad looking father with his youngest boy;

they entered the car with the rest, and the white man first mentioned, who

it appeared was the purchaser along with them. -- When the cars started, the

colored people left behind (slaves, I suppose) came to the door, and kept bowing

farewell until we got out of sight. As we passed a field in which some hands

were at work, the poor fellow just now spoken of as the father, looked out,

and in the most touching manner cried, "farewell! farewell!" adding

with a kind of melancholy satisfaction, "I've got my whole family with

me!" I turned away from the sad scene. If this is the pain, thought I,

inflicted by this traffic, where these ties are ruthlessly sundered!

As such reflections were rushing upon my mind, I was joined by the friend,

with whom I had the dispute the day before, and who had berated the abolitionists

without mercy; "There, Mr. M'Kim, there's a case for you."

"Yes," said I, "a case for you too, Mr. ______. What do you think of it?"

"Oh, it's too bad, it's horrid," said he, "it's DIABOLICAL." And

having thus begun, he continued to assert his abhorrence of the system of slavery

in terms that would have been regarded as very denunciatory, if found in the

columns of the Liberator. Our conversation was at length interrupted by our

arrival of the city depot.

I took lodgings of a private boarding house, and with as little delay as possible,

hastened to the Capitol. Soon after I got into the "House," Mr.

Adams took the floor, in continuation of a speech began on a former occasion,

on our relations with Mexico. He was [ ] in severe terms upon the conduct of

the administration, in taking a hostile attitude towards that government, when

he was interrupted with the annunciation that the House had arrived for the "order

of the day." This was a question which was producing much excitement among

party politicians, but which possessed no interest for me -- further than it

served to elicit exhibitions of the mental powers of distinguished members

of the House, with whose names the nation is familiar. Thus went by the day.

The next morning, in pursuance of the main object of my visit to this place,

I set our for W. H. Williams' Slave-factory.

It was a matter of some doubt to me, as I went along, whether I should get

in. I had been told, that if I wanted to get admittance I must "let on" that

I wanted to buy slaves. This of course I could not do; but made up my mind

to be perfectly candid and practice no kind of deception. I enquired for the

place -- and was directed to it by a colored man; and by the way you need never

be at a loss to find that house, while there is a colored man in Washington

to enquire of. It was in 7th street, between Pennsylvania and Maryland avenues,

not far from the centre of the city, and within a short distance of the stars

and stripes of the capitol. It is a large but lonely and desolated looking

house. I rapped at the door, which after waiting some time, was opened by a

stout, thickset man, dressed in a pea jacket, coat and fur cap, with large

whiskers and stern countenance.

"Is Mr. Williams at home?"

"No, sir, he is in Natchez."

"Have you any negroes now on hand?"

"Yes, sir, we have a few; walk in."

"I don't wish to purchase any -- I merely wish to see your establishment

-- if you have no objection."

"None at all, walk in sir, Mr. Williams is now residing in Natchez -- I

am here as his agent. We have very few slaves for sale of our own -- most that

are here belong to other people." While thus talking, he took me in and

handed me a seat. After some further conversation, into which he seemed to enter

with much freedom, I again observed that I had no "intention of purchasing,

but wished to see, for my own gratification, his establishment, if he had no

objections."

"None at all, sir," and with that he went to a window on one side of

the room, and opened the shutters -- threw up the sash, and invited me to look

out. "This is our 'pen' sir. "Here," continued he, while I surveyed

an area of about 40 feet square, enclosed partly by high jail walls built for

the purpose, "here we allow them to take exercise, and the children to play." As

it was very cold, the 'pen' was empty. They were all down in the cellar, the

agent said. I asked to go down and see them. He accordingly led the way through

a winding passage out into a temporary enclosure which communicates with the

'pen.' He took out of his pocket a key -- opened the lock of a huge iron cross-barred

gate, which admitted us to the space within. He then opened a door which led

us into the 'cellar.' Here, in an apartment of about 25 feet square, were about

30 slaves of all ages, sizes, and colors. I noticed one young girl of about 12

years of age, who seemed quite white, and

another a little child about two years old, of the same shade and one of the

most beautiful children I ever saw. The very small children were gamboling about

unconscious of their situation; but those of more advanced age were the most

melancholy looking beings. The wistful, inquiring, anxious looks they cast at

me (presuming I suppose that I came as a purchaser) were hard to endure. I soon

described the father and his family, that I saw torn away from their former home,

the day before. "Where is your master taking you?" said the agent to

the man in answer to a question of mine put to him of the same import:

"To Alabama - I believe they call it," said

the man in tones of the deepest sadness. His wife sat beside the stove amusing

her infant and never once looked up all the time we were in. Not feeling at liberty

to ask questions of these poor things -- I soon turned away. He then led me to

two other apartments of about the same size; one of them not now used, the other

appropriated as a sleeping apartment to the females. -- "Do all of these

persons sleep down in that cellar?"

"Yes, sir -- all the males: -- they lie upon the floor -- each one has got

a couple of blankets."

"But will that room accommodate so many?"

"O Lord, yes, sir, three times as many! -- last year we had as many as 139

in these three rooms." I could hardly see how this was possible without

their lying on each other. "Well, very few, you say, of these persons belong

to you."

"Only a few, sir, -- most of them are put here by other gentlemen. You see,

we can afford to keep them for 9 cents apiece cheaper than they can at the jail."

"What is your charge?"

"25 cents a day for all except children at the breast." He then showed

me a table at one side of the enclosure where their meals were served up. It

was in the open air, with no other protection than a covering from the storm.

In answer to my inquiries, he told me they took their meals in the open air summer

and winter.

"But" said I, "don't they suffer very much from the cold?"

"O Lord, no, sir, they squat down and eat in ten minutes. We give them plenty

of substantial food -- herring, coffee sweetened with molasses and corn bread."

"How many meals do you give them in a day?"

"Two sir, -- one at 9 o'clock and the other at 3."

After a good many other questions and answers which I have either forgotten,

or deem unnecessary to mention, we returned to the room into which I was first

introduced upon coming to the house: and taking seats by the fire, we continued

our conversation.

I have no room for comment. None, however, is necessity. The guilt! the shame!

the heartlessness! the hypocrisy of this nation! will be thoughts that will

naturally crowd themselves upon the minds of your readers. These are some of

the abominations that exist in the District of Columbia! the national domain

of the American REPUBLIC! within sight of the Capitol and under the stars and

stripes of our national flag! - Aye, the fustian

flag, that proudly waves in solemn mockery, o'er a LAND OF SLAVES!

Yours unfeignedly,

J.M. M'KIM.

Notes

James Miller McKim

Born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, James Miller McKim began lecturing for the

American Anti-Slavery Society in 1836. He became involved with publishing

the Pennsylvania Freeman in 1840, and became corresponding secretary

for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, settling in Philadelphia. J.

Miller McKim was present when the crate containing Henry "Box" Brown was

opened at PAS headquarters. He frequently defended fugitive slaves brought

before the Federal slave commissioner in Philadelphia. McKim and his

wife Sarah attended the execution of John

Brown and accompanied Brown's wife in claiming his body and bringing it

home.

Born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, James Miller McKim began lecturing for the

American Anti-Slavery Society in 1836. He became involved with publishing

the Pennsylvania Freeman in 1840, and became corresponding secretary

for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, settling in Philadelphia. J.

Miller McKim was present when the crate containing Henry "Box" Brown was

opened at PAS headquarters. He frequently defended fugitive slaves brought

before the Federal slave commissioner in Philadelphia. McKim and his

wife Sarah attended the execution of John

Brown and accompanied Brown's wife in claiming his body and bringing it

home.

(Image of J. Miller McKim is from Lamb's Biographical Dictionary of the United States, Volume V, 1903, page 271.)

The

Colored American

African American abolitionist newspaper published in New York City by Samuel

Cornish, Charles Bennett Ray and Philip Bell. It had the support of the

American Anti-Slavery Society--for whom J. Miller McKim was working--which

urged its members to buy subscriptions. McKim's salutation "My Dear

Brother" probably refers to Samuel Cornish.

Harrisburg

Anti-Slavery Convention

Commencing on January 16, 1838 and running most of the week, this was the second

annual convention of state anti-slavery societies to be held in Harrisburg. According

to the Harrisburg Telegraph, the convention was attended by several

hundred delegates at its height, and included men and women, both black and

white. They listened to speeches from Dr. F. Julius LeMoyne of Washington

County and William Burleigh, among others.

The earlier convention, held January 31 to February 2, 1837, was the first convention held

in Pennsylvania by the American Anti-Slavery Society, and it was the

organizing convention for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Delegates

in 1837 included Jonathan Blanchard, Benjamin Lundy, as well as Dr.

LeMoyne and the dynamic speaker Charles C. Burleigh, brother to William,

who spoke in 1838. Proceedings were reported to William Lloyd

Garrison's abolitionist newspaper The Liberator by correspondent

John Greenleaf Whittier.

(A detailed account of how the first Harrisburg anti-slavery convention came about is found here.)

"In

the stage for Baltimore"

The most efficient method of transportation from town to town and city to city,

at this time, was the stagecoach. Rail lines were limited and canal travel

was slow, but stage lines and routes, which transported people quickly and

cheaply, were plentiful in Harrisburg. One of the largest and most successful

stage line companies in Harrisburg was run by Alexander Calder, who had a depot

in Market Square.

"Into

the boot"

The stagecoach boot was a leather storage area for passenger baggage and mail. Most

stages had two boots, one in the rear for baggage and one up front under the

driver's seat, often reserved for mail, which was one of the other important

revenue items for stagecoach lines.

"A

high fellow...runaway slave"

McKim's sarcastic description of the slaveholder's character, as observed by

his fellow passengers, is intended to point out the moral hypocrisy of slavery:

born into a good family, the man is seen as morally upstanding because he does

not drink alcohol. His addiction to gambling is overlooked and the fact

that he owns slaves and is even now in pursuit of one, is not even an issue

to them.

"Barren

and devoid of interest"

McKim seems to have switched his mode of transportation from stagecoach to

train. In this dismissive remark about the Maryland countryside, which

is actually very beautiful, he seems to be transferring the hopelessness of

slavery to the physical characteristics of the land. He is also setting

up the story of the slave family being taken from their home, presumably to

be sold south.

The

Liberator

William Lloyd Garrison began the anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator,

on New Years Day, 1831. From the start it was one of the primary voices

for the radical anti-slavery movement, advocating immediate emancipation for

all slaves. Its strong rhetoric was roundly criticized in the north and

detested in the south.

"Mr.

Adams took the floor"

John Quincy Adams, the sixth president of the United States (1825-1829), returned

to national politics after the presidency as an elected representative from Massachusetts,

serving from 1830 until his death in 1848. He was an eloquent anti-slavery

voice in the House of Representatives, fighting against the "Gag Rule," which

stifled anti-slavery petitions for eight years.

In the speech mentioned by McKim, Adams is railing against Texas, which by now had declared its independence from Mexico and had re-instituted slavery, outlawed by Mexico in 1829. Southerners were eager to annex this very large territory into the union, making four or five new slave states.

W.

H. Williams' Slave Pens

Slave dealer William H. Williams kept a prison, from which he housed and sold

slaves, at Seventh and Maryland Avenues in Washington, DC. He often advertised

for slaves in Washington newspapers. One typical ad stated in part "Cash

for 300 Negroes. The highest cash price will be given by the subscribers

for Negroes of both sexes, from the ages of 12 to 28."

"Who

seemed quite white"

One of the telling remarks of the inherent racism found even in anti-slavery

circles is the preoccupation with slaves of light complexion. Even

dedicated activists such as McKim fell victim to this skin-color trap.

Author Harriett Beecher Stowe made her key enslaved character in Uncle Tom's Cabin, Eliza Harris, light skinned to evoke even more sympathy from readers.

To

Alabama

Many of the slaves held by W. H. Williams in his Seventh Street prison were already

sold, awaiting delivery to new owners in the deep south. Washington and

Baltimore slave dealers often had deep south business connections and acted as agents for buyers in Mississippi, Alabama

and Louisiana.

(Click here to read an advertisement placed by W. H. Williams.)

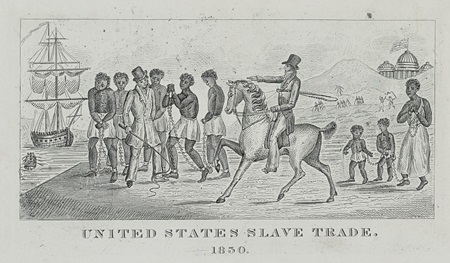

"United States slave trade, 1830." Print: engraving on wove paper; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

The fustian flag

McKim's description of a "fustian flag"--high sounding and boastful

of a liberty that extends only to white people--flying proudly over the national

Capitol only blocks away from a filthy, overcrowded slave pen, is reminiscent

of the outrage expressed by his close friend and American Anti-Slavery Society

founder William Lloyd Garrison for another American symbol, the Constitution.

As early as 1832, in the columns of The Liberator, Garrison had described the Constitution as "dripping ...with human blood." In later years, Garrison would describe the Constitution as "a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell." Finally, on July 4th, 1854, at an anti-slavery picnic in Framingham, Massachusetts, he publicly burned a copy of the U.S. Constitution.

J. Miller McKim's rejection of blind patriotism in the name of unity found its ultimate embodiment in the actions of John Brown in 1859, whose body McKim helped bring home for a martyr's funeral two years before the country tore itself apart in war.

Covering the history of African Americans in central Pennsylvania from the colonial era through the Civil War.

Covering the history of African Americans in central Pennsylvania from the colonial era through the Civil War.

Support the Afrolumens Project. Read the books:

The Year of Jubilee, Volume One: Men of God, Volume Two: Men of Muscle