Study Areas:

Image from the Harrisburg Daily Telegraph, 23 June 1862.

Harrisburg Cemetery Grave is first Known Confederate Burial in Soldier's Lot

The graves in the Soldiers' Lot in the Harrisburg Cemetery lie in straight rows, almost as if the dead are lined up on the parade ground, with official tombstones standing at attention with true military precision. Thirteen of those stones are unlike the others, sporting a distinct pointed arch that signifies the grave of a soldier of the Confederate States of America. All are fatalities, from wounds or disease, who died in Harrisburg military hospitals as prisoners of war.

In his 1990 book about Camp Curtin, William J. Miller lists the names and gives details about each of these Southern soldiers, noting "all of the Confederate fatalities came in the months after Gettysburg." Miller makes reference to the hundreds of Confederate soldiers captured after that great battle and imprisoned at Camp Curtin, and to those wounded Confederates who were treated in one of several military hospitals located throughout the city. Because those Southerners were sent on to official prisoners-of-war camps soon after their capture, or after their recovery in the hospital, and because the tombstones record the date of death of each Confederate soldier but one, Miller concluded, not unreasonably, that all of the Southern war dead buried in the Harrisburg Cemetery Soldier Lot were veterans of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Of course they were not the first southern prisoners-of-war brought to Harrisburg. Miller wrote about the first prisoners brought to Camp Curtin in mid-June 1862, who caused a sensation among local residents. He wrote "When the citizens of Harrisburg learned the Rebels would be coming through their city, their desire to see the vaunted foe surpassed almost all else. They rushed about like children at a circus. Long before the first trainload was in view, people were lining the tracks all the way across the bridge to Bridgeport on the west bank of the river opposite Harrisburg, hoping to get a glimpse of 'Jeff Davis's men.' " 1

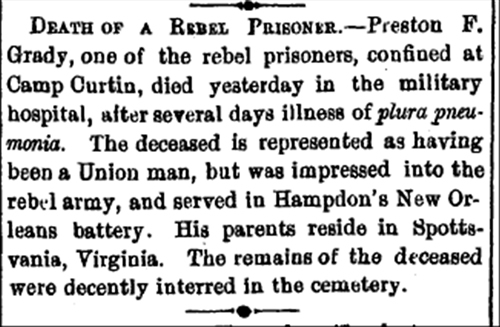

While most of these men would be shipped out to Federal prison camps in a few days, one of them, an artillerist named Preston F. Grady, would be kept in Camp Curtin's hospital because of ill health. MIller wrote that the majority of the prisoners were described in the newspapers of the day as undernourished and filthy, and it should not be surprising that a few suffered from sickness because of it. 2 Gradys' condition apparently worsened, and he died within a week of arriving in the city. While numerous Union soldiers had died in the city hospitals, Grady was the first Rebel to die in Harrisburg, and a local newspaper, the Pennsylvania Telegraph, ran the following article (image also reprinted above):

Death of a Rebel Prisoner--Preston F. Grady, one of the rebel prisoners, confined at Camp Curtin, died yesterday in the military hospital, after several days illness of plura pneumonia. The deceased is represented as having been a Union man, but was impressed into the rebel army, and served in Hampden's New Orleans battery. His parents reside in Spottsylvania, Virginia. The remains of the deceased were decently interred in the cemetery.3

The cemetery referred to was the Harrisburg Cemetery, whose newly opened Soldiers' Lot was already filling rapidly by this time. Grady would be the first Confederate to lie in ranks beside the Union soldiers who had died in the city. His grave was probably marked with a simple wooden headboard, just like those used to mark the graves of the Union soldiers. If any regimental information or date of death were recorded on Gradys' marker, it had probably worn off by the time it was replaced by a permanant granite marker in 1906. That information was lost until recently, and we now know that Grady was not a casualty of the Battle of Gettysburg, but was one of the thousands of victims of disease, and was the first known Confederate soldier interred in Harrisburg Cemetery.

The Telegraph identifed Grady's military unit as "Hampden's New Orleans battery." There does not appear to have been an artillery battery by that name, and the editor of the Telegraph, George Bergner, likely misinterpreted information provided about the dead man and mixed up several Southern artillery units that were active at that time, the Washington/Hampton Artillery, the Hampden Battery, and the Washington Artillery of New Orleans, to incorrectly attribute Grady's war service.

Recent research, however, shows that Preston F. Grady actually served in Company C of the 38th Virginia Light Artillery, Read's Battalion. He had attained the rank of sergeant when he died in Harrisburg.4 The Telegraph's statement that Grady was a "Union man...impressed into the rebel army" was most likely patriotic filler, probably contributed by a nurse or friend who looked after Grady in his final days and learned a few details of his personal life, such as the hometown of his parents. Such a person may have developed a sympathetic bond with the young artillerist and would not have wanted him to be portrayed in a northern newspaper account in the vitriolic language so commonly used.

We now know more about Artillery Sergeant Preston F. Grady than we did years ago. He is listed in the government document "Register of Confederate Soldiers and Sailors who Died in Federal Prisons and Military Hospitals in the North. Compiled in the Office of the Commissioner for Marking Graves of Confederate Dead. War Department, 1912." On page 451 is the "List of Confederate soldiers who, while prisoners of war, died at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania." Grady is listed alphabetically, with the other twelve Southerners who died and were buried in Harrisburg during the war years. Unlike the other twelve men, and unlike most of the more than 25,000 names in the 665-page document, Grady has no date of death listed. 4 We now know he died on June 22, 1862. We would like to know more.

Notes

1. William J. Miller, The Training of an Army: Camp Curtin and the North's Civil War (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing, 1990). The names of the Confederate burials appear in the notes to chapter five, on pages 299-300. The quote about the excitement created in the city by the appearance of the Southerners is on page 100. This book has been re-released under the title Civil War City: Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 1861-1865.

2. Ibid., 100.

3. Pennsylvania Telegraph, 23 June 1862.

4. Office of the Quartermaster General, Register of Confederate Soldiers, Sailors, and Citizens Who Died in Federal Prisons and Military Hosptials in the North 1861-1865, p. 451.

Other Articles