Enslavement

Enslavementto freedom

Moving Through and Meeting the Challenges

of the Twentieth Century

Study Areas

Earliest Known Box Score for Harrisburg Black Baseball

Pythians vs. Monrovians

October 20, 1867

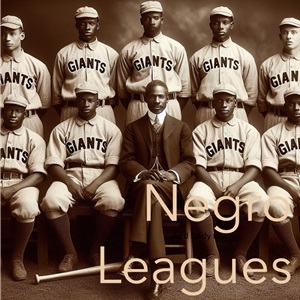

The above box score is reproduced from Ted Knorr and Calobe Jackson's article, "Blackball in Harrisburg", 1998. It was originally printed in Commemorative Program: 2nd Annual Negro League Commemorative Night,produced for the SABR Negro League Committee Research Conference, August 7-9, 1998 in Harrisburg. African American baseball teams of the 1860's and 1870's, like their white counterparts, were composed of men who viewed their participation as a pastime, and games as friendly recreational affairs separate from their vocations. The fact that most of the earliest teams were composed of either whites or African Americans, and that very few mixed-race teams existed, may have had more to do with the racial segregation that permeated Victorian society at the time, rather than from any rules or customs associated specifically with baseball. It is precisely because early baseball was considered a social event that the earliest "ball clubs" were formed from men who were already members of racially segregated social groups. As those groups were racially exclusive, so were the ball clubs formed from their members.1 That would change shortly. The Philadelphia Pythians, one of the earliest ball clubs out of the City of Brotherly Love, applied for membership with the National Association of Base Ball Players in 1867 but was denied membership in that all-white organization. As Ted Knorr and Calobe Jackson write, in "Blackball in Harrisburg:"

Although the teams might be segregated, the games themselves sometimes involved a white team as an opponent, but more often both teams and their spectators were Black. With a limited number of teams formed in this early stage of the game's history, Black teams often had to travel to other cities for opponents, as is the case in the game between the Pythians and the Monrovians. Knorr and Jackson quote a letter written by the Monrovians' secretary, George Galbraith, to the Philadelphians, in which he expressed the club's "desire to engage with you in a match game of ball." Galbraith's letter resulted in the game recorded in the box score at the beginning of this article.3 Although we know the results of that historic game, and have the names of the players, we can only positively identify one of the eighteen named players: "Catto" is Octavius V. Catto, who played second base in this game for the Pythians. Knorr and Jackson identify this player by name,4 and further confirmation is provided by Philadelphia historian Andy Waskie in his article about Catto, "Forgotten Black Hero of Philadelphia." Waskie notes that Catto "was equally involved in sports as the founder and captain of the finest baseball team in the city, the 'Pythian Baseball Club,' where he played an outstanding shortstop position."5

Octavius Catto was an educator in Philadelphia, teaching English Literature, Classical Languages and Higher Mathematics at the Institute for Colored Youth in the city. He later became principal of that institution, which is now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania. His political activities were equally diverse. He helped found the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League and was active in the 4th Ward Black Political Club and the Union League Association. Catto was a leader in the fight for equal access by Blacks to the public streetcar system in Philadelphia. Tragically, it was Catto's political activities in the volatile elections of 1871 that led to his murder at the hands of roaming thugs near his South Street home.6 On the Monrovians team are several names which show up in federal census records for the city. Saunders might be George W. Saunders of Harrisburg, active in the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League in the mid-1860's. George Saunders does not show up in the 1870 census for Harrisburg, though. The 1870 Federal Census for 1870 shows two African American men named William Lane living in Dauphin County, both in Susquehanna Township. In the same area is listed a Lewis Gray in 1870. There are several women named Gray in Harrisburg in 1870, but no adult males. Going back to the 1850 census, we find a William Gray, born in 1844, living with his family, including father John Gray, in Harrisburg's North Ward. Julian Burtin and Richard Burton both lived in Harrisburg's Sixth Ward in 1870, but no "H. Burton." There are no listing for any Lanes with given names beginning with the letter "D" in Harrisburg, but there is a George Lane in the city's Sixth Ward.7 Two of the names on the Monrovians' roster are more familiar than the rest, however. Pople, at shortstop, and Chester, at third base, are names well known in Harrisburg history. Joseph B. Pople was a well respected member of the city's African American community, active in politics, Underground Railroad activities, and remembered for his outstanding role in securing freedom for a captured fugitive slave in 1850. During a standoff between some Virginia slaveholders and a crowd of Harrisburg Blacks at the county courthouse, Pople charged up the steps of the courthouse and pried open a large iron door at the entrance to the jail, allowing a captured slave to slip away into the crowd. The Virginians beat the 31-year old Pople, but the slave escaped in the confusion.8 Born in 1819, Pople would have been 48 years old for the game with the Pythians. Although Pople, who was a laborer during most of his active life, was probably vigorous enough to play, the shortstop may actually have been his son Samuel, born in 1837.9 Another possibility is that the position was played by Joseph G. Pople, believed to be the son of Joseph B. Pople. Like his father, Joseph G. was active in Harrisburg's Black community, holding the post of Worshipful Master from 1900 to 1901 with the Chosen Friends Lodge Number 43, Free and Accepted Masons.10 At third base was a member of the Chester family, although we know it was not Thomas Morris Chester, who was studying law in England at the time of the game. Yet the influence of T. Morris Chester on the team is at once reflected in the name. T. Morris Chester was a tireless promoter of Liberia as a land where Black could develop themselves free of the limits imposed by American racism. He spent several years in the capital, Monrovia, making four trips there in the 1850's, first as a student and later as an teacher and the publisher of a newspaper, Star of Liberia. After the war, T. Morris Chester was possibly the most accomplished member of Harrisburg's Black community, and there is little doubt that the team name, The Monrovians, is a tribute to his work.11 So who was the Chester at third base? It could have been the younger brother of T. Morris, David Chester, who is believed to have been in Harrisburg at the time. Historian William Henry Egle also mentions another person, Moses Chester, who would have been close to the same age as Thomas Morris and David, but little else is known about Moses.12 Finally, the secretary of the team, George Galbraith is identified by Calobe Jackson, Jr., Harrisburg historian and Negro Leagues researcher, as the son of Bishop George Galbraith, of the A.M.E. church in Harrisburg. George and his mother, Elizabeth, are buried in Harrisburg's Lincoln Cemetery.13 Although the identities of many of the players of that early intercity Black baseball game remain uncertain, the game remains important to Harrisburg history because it is the precursor to a long and vibrant heritage of baseball in the capital city. Notes:1. African Americans, socially isolated by segregation, formed their own schools, churches, banks, literary and self-improvement societies, fraternal organizations, firefighting companies, newspapers and many other institutions of a free, vibrant community. See W. E. B. DuBois, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1899), esp. chapters IV, IX and XII; and Julie Winch, Philadelphia's Black Elite: Activism, Accommodation, and the Struggle for Autonomy, 1787-1848 (Temple University Press, 1988), esp. chapter 1. 2. Ted Knorr and Calobe Jackson, Jr. "Blackball in Harrisburg." 1998 Commemorative Program: 2nd Annual Negro League Commemorative Night. Harrisburg, PA, 1998. n.p. To read Knorr and Jackson's original article, click here. 3. Ibid. 4. Ibid. 5. Andy Waskie, Ph.D. "Biography of Octavius V. Catto: 'Forgotten Black Hero of Philadelphia.' "Octavius Catto Biography--Andy Waskie." March 26, 2002. Afrolumens. <https://www.afrolumens.com/rising_free/waskie1.html> 6. Ibid. 7. For George Saunders' involvement with the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League, see "Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League, held in Harrisburg, Aug. 9th and 10th, 1865." The Christian Recorder, December 02, 1865. Accessible Archives.<http://www.accessible.com/>. For information from the federal census records, see microfilm records at the Pennsylvania State Archives, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. "1870 Federal Census, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania," and "1850 Federal Census, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania." 8. Gerald G. Eggert. "The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg: A Case Study." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 109 (October 1985), 540-543. 9. "1850 Federal Census, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania." Tombstone inscriptions, Lincoln Cemetery, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. (Joseph Pople died November 28, 1895. His son Samuel lived 1837-1915.) 10. "History of Chosen Friends Lodge No. 43, F. & A. M." Web page of Chosen Friends Lodge No. 43, Harrisburg, PA. (http://hometown.aol.com/Chos43/index.htm), June 21, 2002. Editor's note: This link was apparently defunct as of January 29, 2005. 11. R. J. M. Blackett. Thomas Morris Chester, Black Civil War Correspondent. Louisiana State University Press, 1989. Republished by Da Capo, Press, Inc., pp. 12-29; Knorr and Jackson. 12. William Henry Egle. Notes and Queries, Annual Volume, 1899. p. 184. 13. Calobe Jackson, Jr., email correspondence, June 21, 2001. Jackson notes that the younger George Galbraith was "one of at least two African American Enumerators of the 1900 census." Works Cited:Blackett, R. J. M. Thomas Morris Chester, Black Civil War Correspondent. Louisiana State University Press, 1989. Republished by Da Capo, Press, Inc. DuBois, W. E. B. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1899. Reprinted 1996. Eggert, Gerald G. "The Impact of the Fugitive Slave Law on Harrisburg: A Case Study." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 109 (October 1985). Egle, William Henry. Notes and Queries, Annual Volume, 1899. Knorr, Ted and Calobe Jackson, Jr. "Blackball in Harrisburg." 1998 Commemorative Program: 2nd Annual Negro League Commemorative Night. Harrisburg, PA, 1998. n.p. Waskie, Andy, Ph.D. "Biography of Octavius V. Catto: 'Forgotten Black Hero of Philadelphia.' "Octavius Catto Biography--Andy Waskie." March 26, 2002. Afrolumens. <https//www.afrolumens.com/rising_free/waskie1.html> Winch, Julie. Philadelphia's Black Elite: Activism, Accommodation, and the Struggle for Autonomy, 1787-1848. Temple University Press, 1988. Further Reading:"Blackball in Harrisburg" by Knorr and Jackson Negro Leagues in Harrisburg, Part 1: "Early Games and the Independent Era" Negro Leagues in Harrisburg, Part 2: "League Play and Major League Integration" Negro Leagues in Harrisburg, Part 4: "The Olympic - Tyrolean Rivalry of 1876" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Afrolumens Project Home | Enslavement | Underground Railroad | 19th Century | 20th Century

Original material on this page copyright 2024 Afrolumens Project

The url of this page is https://www.afrolumens.com/century_of_change/baseball3.html